- Home

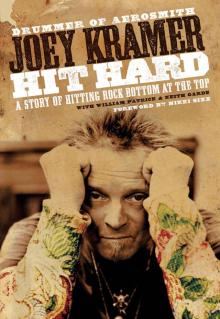

- Joey Kramer

Hit Hard Page 6

Hit Hard Read online

Page 6

So Raymond put it on the turntable, and we all started listening. Steven had more sophisticated musical tastes and had his finger on the pulse. What he introduced us to this day was Jimi Hendrix’s third album, Electric Ladyland. Steven sat himself down on a drum stool in the corner of the room and just went off into this groove.

It took all of sixty seconds for me to completely forget about cruising with Johnny. All of a sudden I couldn’t wait to go out and get that record and start learning all that shit. I was completely blown away by Hendrix, and especially by Hendrix’s drummer, Mitch Mitchell. That dude was from another planet as far as I was concerned. The songs were great, and Hendrix’s singing was great, and the sound of his guitar was simply miles and miles beyond anything I’d ever heard before. The whole thing made me feel higher than the drugs, and even if I’d been clean and sober, it would have sent me flying.

I left Raymond’s, went out, bought the record, and took it back to my room. I listened to every track over and over and over again, and I learned every lick and every beat. I listened to it all the time, day and night, night and day, and by the time I’d worn that vinyl out, I knew every bit of it backward and forward.

And then came the next album, Axis: Bold as Love, which completely sealed the deal for me with Hendrix and Mitch Mitchell. It didn’t take long before I could play every beat on every song on that album too. It was unusual then for the drum sounds to be so powerful. This was actually one of the first recordings where I could hear the drums distinctly enough to really tell exactly what the drummer was doing. Mitch was just playing so much, and that’s what I was getting into—his adding all those fills and chops in addition to timekeeping.

I was ready to apply this new understanding of what was possible with a set of drums. The first chance I had to really try it out was with a band I got into after Strawberry Ripple called Nino’s Magic Show. Jack Wizner, who came from Strawberry Ripple with me, was the guitar player, and he used to pick me up and drive me out to rehearsals at the keyboard player, Larry’s, house in New Jersey.

This was 1968, and things at home sucked so bad that I was going out of my mind, but here with these guys I could be myself. More than that, I could be myself making something happen musically. I picked up the phone, called my parents, and told them I wasn’t coming back.

My mother started crying. “How can you treat us this way?”

Then my dad got on the line, but instead of tearing me a new asshole, he tried to sound like the guy on Father Knows Best. “Son, you really need to come home. Your mother’s hurt. You’ve made your mother and me…”

He told me everything would be okay, but everything wasn’t okay, and it wasn’t going to be—I knew that, and he probably knew that too. My dad was the muscle that enabled my mother’s need to control. If I made her feel bad, he was the one to make me pay by beating the crap out of me. I was sick of this shit, and I decided I had to do something about it.

“I’m not coming home,” I repeated.

“How long can you stay there? You don’t have any money.”

“I’ll be fine. I’m just not coming home.”

I stayed out there for most of the summer, living on Spam at Larry’s parents’ house and playing rock ’n’ roll. And I think it really drove my parents nuts that, for the first time, they really had no say. They didn’t even know exactly where I was.

By the time the summer was over, I’d pretty much worn out my welcome in New Jersey, and I was pretty sick of Spam, so I finally relented and came back home. I think my parents where sufficiently glad to see me that they stayed fairly cool for a while. I lived at home, did my senior year at Thornton-Donovan, and, miracle of miracles, in June I actually got my diploma.

Around that time not much was happening for me musically. Nino’s Magic Show had sort of faded, so I spent the summer after graduation indulging my other passion—drugs.

It was 1969. The parents of another friend of ours, Steve Dwyer, were going to put their house on the market in the fall, and they gave us the run of the place for the summer—Steve, my buddy Richard Guberti from New Rochelle Academy and me. So here I was, living in a big house with a pool in Harrison, New York, and my summer job was dealing, and I was doing pretty well. Steve’s mother was the owner of the Sabrett Hot Dog empire, and there were cases of hot dogs all over the place. We must have eaten tons of hot dogs, and owing to the influence of chemical enhancement, we got very creative. We tried every imaginable combination of hot dogs: hot dogs with peanut butter, hot dog Hostess Twinkie sandwiches, hot dog and tuna casserole, a la mode…I can’t, and don’t really want to remember much more, but suffice it to say, our summer was, among a few other things, a veritable drug-assisted, hotdog extravaganza.

Father and son “lookin’ good”; Eastchester, NY

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

Richard Guberti and I based out of the house in Harrison that summer. His parents bought him a 1969 MG-C for graduating high school and we would drive it up to Boston to cop a couple of pounds of weed, then drive it down to New York City. We would sell it in Manhattan, pick up a couple of thousand caps of mescaline, then ferry that back up to Boston. The mescaline caps were camouflaged, stuffed in large candle canisters, with a couple of dozen candles to a case. We’d pack the goods into the MG, drop a hit of mesc for the road, and then count out the number of joints we calculated it would take us to smoke our way back to Boston. Very scientific. Once home, we would only sell what we had to in order to cover the cost of what we would give away to our friends and what we would eat ourselves. We did everything we could to consume whatever “extra” merchandise was on hand at any given moment.

Next to the pool cabana there was a shed, and inside the shed was diving gear: tanks and flippers and wetsuits. One day we had a big gang over, and we were tripping; I decided to enhance the experience by putting on all that SCUBA shit, then getting into the pool.

Everybody else was just hanging around outside on the lounge chairs, staring at leaves or counting their toes, but I had this tank on my back, and I was fiddling with the regulator, teaching myself how to breathe through the mouthpiece. Then I was under the water, watching the bubbles rise, totally tripping all by myself. I felt like I was in one of those sensory deprivation chambers, only with the thing set to serious fucking overload. The water was going from orange to purple and back to blue green, and the tile walls kept expanding and closing in and then rotating up over my head into the sunlight.

Because I was under the water—not to mention completely tripped out—I didn’t notice when it clouded over, when the lightning started, or even when it started to rain. But by the time I surfaced, everybody else had run up to the house. I stood up out of the water, looked around, and thought, What happened? Where’d everybody go?

So I came out of the pool and started walking toward the house, the rain pelting me, thunder pounding, wearing these flippers and a mask and the big tank on my back. I’m not sure I had a clear concept of whether I was still in the pool or on dry land. It was a fairly steep hill to get to the house, and the lawn was slippery, and I was wearing flippers, so I kept falling down. And when I looked up, I could see everybody else, warm and dry in the living room, huddled at this big picture window, watching me, pointing at me, and laughing their asses off. I’m sure I must have looked pretty funny, but still it sent a chill right through me. I felt like the outcast. I hated that feeling but it came rushing back to me, so what I did was my classic “hide” response. I turned around and went back down to the pool and lowered myself back under the water.

My grades all through school had been crap. I had no interest in academic pursuits, but even so, my parents insisted that I go to college. Their son had to be a college graduate. If for no other reason than to keep the peace, I signed up for the fall at Chamberlain Junior College in Boston. The school meant nothing to me, but I was pretty psyched that in just a few weeks I was finally going to be away from all the bullshit at home.

&nb

sp; In August as a kind of freshman orientation to the freedom to come, some buddies and I decided to attend this concert upstate. Word had spread that there were going to be maybe thirty bands—and big name bands at that—out in some farmer’s pasture. The posters all over New York said, 3 Days of Peace & Music. All I needed to hear was that the Who was going to be playing there, and there was no way that I wouldn’t be there too.

On the 14th of August, 1969, I was barreling up the New York State Thruway in a red Oldsmobile convertible, totally stoned, with my friends Howie Brooks, Jerry Elliot, and Joel Van Blake. From the looks of the building traffic, this event was going to be an even bigger deal than we’d thought. It was turning into some kind of mass migration, with every freaky, Age of Aquarius, longhaired kid in the Northeast hanging out a car window, flashing me the peace sign. For that one moment in time we were all heading in the same direction.

We got to the Yasgurs’ farm early, before the cops closed off the thruway, so we actually made it onto this farm in Bethel, New York, where the “3 Days” was all supposed to happen. Tickets were eighteen bucks, six dollars for each day. We figured we’d buy these when we got there, but they were for sale only back in the city, so we bribed a couple of the gate guys with Quaaludes and some weed, and they let us in.

Later that day the number of humans converging on the scene was so huge that the state police had to shut down the thruway. The makeshift fences came down, and anyone who wanted to just walked on in. There were half a million people there. It was amazing—our world was changing, and Woodstock was the soundtrack of this great cultural shift.

We drove across the pasture and set up our little camp at the crest of the hill overlooking the stage.

I could see these huge towers with speakers on top going all the way up the slope. As the crowd kept coming onto the grounds and settling in, it was like the gathering of the tribes, or maybe some kind of costume party, with feathers and face paint, and chicks in granny dresses, and guys with beards and hats that made them look like the Union Army on maneuvers, not a bunch of hippies getting ready to fuck their brains out listening to Country Joe & the Fish.

Joel had brought this big blue tent, and we had Howie’s Oldsmobile right next to it, and the four of us inside. It was maybe ten-foot square, and it had a floor, and you could even stand up in it. More and more of these beat-up psychedelic school buses appeared all around as the hippie pioneers circled their wagons. Then some mangy-looking guy suddenly showed up at our door. I have no idea where he came from, but he had that tanned, dirt-encrusted look like he’d been on the road for about twelve years. He asked if he could stay with us. We were pretty dubious, but when he pulled out this hunk of hash the size of a softball, we all said, “Sure. That’s your corner.” We let him stay in the tent, and he kept us high on Red Lebanese hash—moist with cannabis resin—you could almost get off just looking at it. We ate it, and we smoked it, and then I spent the next forty-eight hours lying down on the floor of the tent, looking down through the rain toward the stage. My head was propped up on my arm, and the hash pipe was in my mouth. I’d light the pipe and take a hit, and then I’d nod out. Then I’d open my eyes again, stuff the pipe back in my mouth, and light it up again. Between the Tuenols, Seconals, the blotter acid, and the hash, it just went on and on.

By the time the Who made it to the stage, which was 4 a.m. Sunday, I was so out of it that Howie and Jerry had to hold me up, with one of my arms over each of their shoulders.

I had taken Tuenols to kind of mellow me out and bring me down off the acid, but all they did was make everything slow to a crawl. When somebody spoke to me, I could see the words coming out of his mouth like in a cartoon, with the alphabet floating by in slow motion.

The Who played twenty-five songs in a two-hour set that lasted until the sun was just about up. When Grace Slick and Jefferson Airplane took over, I decided to go for a swim. There was a pond on the other side of the woods, the woods into which everyone was running off to take a shit because there weren’t enough toilets. I passed through this big muddy quagmire—I hope it was mud—and who should I bump into but Raymond Tabano, the king of chunko, the “weekend-kit” entrepreneur.

This encounter with Raymond diverted me from my mission of a sunrise splash. We decided to head over to where his tent was set up, which was near the hog farm. He was carrying these Lebanese Temple Balls, which got me even more fucked up, and I was feeling truly transcendental when, walking across this field, I saw somebody in the distance, sort of gliding toward me in slow motion.

I really liked the image of his arms moving back and forth and his legs going up, down, up, down, and I kept walking, while this other person kept gliding toward me, and as we got closer, I realized it was, once again, Steven Tallarico.

I shit you not. They say that when the student is ready, the master will appear. All I know is that Steven Tallarico kept popping up all over the place. It would be another year or so before he and I started getting together on a more regular basis, but when we did, we and a few other guys I would soon meet made a little bit of music history.

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

BROWN RICE AND CARROTS

3

In September 1969, only a couple of weeks after Woodstock, I was out of my parents’ house and living in Boston, a freshman at Chamberlain Junior College. The first thing I did was grow my hair, but instead of “down to there,” it was more “out to here” in a big frizzy mop. With the crowd I hung with in high school, I was the only guy without long hair; here I was the only guy with it. So I was thinking this was not going to be such a great match, Chamberlain and me.

But then I met my first real sweetheart, a girl named Gracie Schwartz, and I fell head over heels in love. Her best friend, Margorie, was hooked up with my roommate, Jerry Notaire; the girls were a little older than us and well connected and able to get us really high-quality drugs. Mostly, they really liked to fuck. So, at a second look, college was not too bad.

Gracie and I spent most of the fall semester in our dorm room, fucking and stoned out of our minds. Life was excellent. But then Jerry and I decided that it could be even better so we launched a campaign to fight the school’s policy of gender segregation. In other words, we wanted to be able to fuck and suck and get stoned with our girlfriends, in our dorm rooms, anytime we wanted, without having to go to all the trouble of sneaking the girls past the dorm counselors. To listen to us rant and rave, you’d have thought it was the My Lai massacre that had us all worked up. We printed up a bunch of flyers and distributed them all over campus. We stood in front of the buildings, yelling, “Don’t go to class! Boycott your classes!” And boom—we had an actual strike on our hands.

Before the fall semester was over, we had attracted a lot more attention to ourselves from the administration watchdogs than to our cause, and we got caught with the girls in our room. Over Christmas vacation I was at Gracie’s house in New Jersey when I called home to speak to my mom. Even for my mother her voice was pretty cold, contained, and controlled. She told me about the letter they received from Chamberlain saying I was not to come back.

Then my dad got on the phone, and he’d pretty much blown a gasket. “This is the last straw. From now on, you’re on your own.”

“Fine,” I said. I was nineteen years old, and the calendar was just about to roll over to a new decade.

My days at home were over, and so were the sixties. Platform shoes and disco were just around the bend, and the “Peace and Love” message had taken a pretty good hit from the Manson Family murders and the Stones concert at Altamont where the guy got knifed on camera. Richard Nixon—not Bobby Kennedy or Gene McCarthy—was in the White House, and the Moral Majority was primed and ready to pull the country back to a right–wing conforming status quo. In just a few more months the Beatles would be breaking up. A few months after that Hendrix would overdose, followed by Janis Joplin, and then Jim Morrison. My response at the time was to make the most of sex, drugs, and rock

’n’ roll…

When Jerry and I came back to Boston as “former students,” we proceeded to get an apartment together at 855 Beacon Street. This was in the Fenway area just out of Kenmore Square, about a bong’s throw from Boston University. Mrs. Shapiro, our landlady, was always bugging us for the rent and also to take down the peace sign hanging in our front window.

I got a job at the Prudential Insurance Company, making $56 a week, running an A. B. Dick machine in the duplicating department. To subsidize the slave wages, I picked up some cash dealing in weed and mescaline.

The head of my department at Prudential was a big black guy who stood about six foot eight and went by the name “Tiny.” We got to talking one day, and he told me he sang baritone in a soul group called the Unique Four. When I mentioned that I played the drums, he said, “You gotta come check us out.” The Unique Four had a backup band, and it so happened they were looking for a drummer.

A few days later, Tiny was outside my door in a van, waiting to take me and my drums over to this place in Roxbury where he and the group rehearsed. I had no idea where I was going. I didn’t really know Boston, and I had no clue that Roxbury was a neighborhood where I was going to be the only white man within about two miles. It made no difference to me, but I think I must have been slightly conspicuous with my white-fro hair and my Captain America shirt.

I went into this sort of grungy apartment and set up my drums in the living room. I was diddling around and warming up as the other musicians started wandering in. I definitely got the feeling that some of the band members weren’t real happy I was there. I could almost hear them asking, “Who the fuck is this white-assed, blue-eyed mother fucker who not only wants to play with us, but wants to play the drums?”

Hit Hard

Hit Hard