- Home

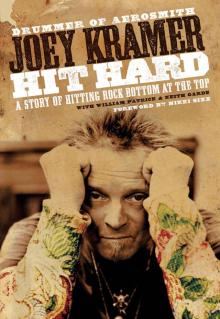

- Joey Kramer

Hit Hard Page 11

Hit Hard Read online

Page 11

In 1976 we were also nominated as Best New Group at Don Kirshner’s rock awards, which was a pretty good joke since we had been around since 1970. The winners were Hall & Oates. Joe’s Elyssa—by now his wife—said they sounded like a breakfast cereal.

My entire adult life had been about playing music, then getting high, then sitting around with the guys bullshitting and wasting big chunks of my time. But by now we’d reached a tipping point that Joe Perry summed up this way: we’d became drug addicts dabbling in music, as opposed to musicians dabbling in drugs.

Joe liked me to provide drum rhythms while he worked out guitar riffs, so I used to go over to his house to work—just the two of us. This was when he lived in Chestnut Hill, out by Boston College, and I can remember being up until two or three o’clock in the morning getting high before we ever went downstairs to start playing. I don’t know that anything useful ever got done in those sessions. Which is sort of the larger tragedy in a nutshell. We were really committed to being musicians, but the commitment to drugs just flushed that down the toilet. Sometimes I wonder how many more great songs we could have written back then if we had been clean and sober.

Even if I never did drugs on a show night, I was never completely clean. It made no difference what I’d do on the eleventh day; if I’d been doing drugs for ten days and drinking for ten days, I was still going to be fucked up.

My drug use was making my life, and all of our lives, unmanageable, but I never questioned it. I never asked myself why I was behaving this way or thought that there was even a question to be asked at all. I would just put my head down and plow on through—only now it was through mountains of coke and everything and anything else I could find to cut that edge.

All in all, I still carried, and was driven by, a certain pride in musicianship. In ’76, we opened for the Faces, with Jeff Beck as the “special guest.” He had just come out with his first instrumental album, Wired, and his band on that tour was Max Middleton playing piano, Wilbur Bascomb playing bass, and Bernard Purdie playing drums.

Tom and Joey with their Ferraris

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

Bernard Purdie—everybody called him Pretty Purdie—was a studio guy, the drummer who originated the fatback beat. He played on Supremes records and all the Motown stuff, and I used to sit and watch him every night and study him. He used to come out and watch me, too, which used to make me really uptight. But one night he came back to the dressing room before the show and asked me if I could get him an Aerosmith T-shirt.

I said, “You want to wear an Aerosmith T-shirt?”

He goes, “Yeah, because I like you, man. You play like a black man.” Later, I came to find out that he had a thing about not liking white people, so those words from him were really a high compliment. And that kind of high lasted for me. It made me feel better later whenever I’d remember it.

The following year we toured Japan under the guidance of the legendary promoter Mr. Udo. We did seven sold-out shows with Bow Wow as the opening act.

Back in those earlier days we took the train, lugging all our equipment from town to town. It was hard to get drugs over there, which may be the reason that we did such good shows. Japan was still very uptight in those days, the kind of place where you couldn’t get into the bathhouses if you had tattoos because only gangsters had tattoos.

I went to Asia with a suitcase and a shoulder bag, and I came back with half a dozen suitcases and a couple of lockers. The promoters used to give us stuff like robes and shoes, and I bought clothes and incense and sake. I even bought a Japanese wedding dress just as a decoration for my house. I also bought a couple of silk baseball jackets with embroidered tigers on the back.

Years later, the Rolling Stones would dis Mr. Udo by cutting him out as promoter and doing business directly with the Domes (indoor stadiums where Japanese major-league baseball games are played). To prove no one fares better without Mr. Udo, he used our next tour after the Stones had dissed him to get his revenge by showing them just how big he could make a band. Mr. Udo promoted us with a vengeance. We broke every attendance and ticket-price record for any band that toured in Japan, ever. Today when we go to Japan, we hole up in one hotel and fly to the eight or so biggest stadiums in the country for each of the shows on the tour.

Once we returned to the States, we were on the line to produce another record, so we rented a mansion up in Westchester called the Cenacle. It had been built by the Broadway showman Billy Rose, then turned into a retreat house for an order of nuns called the Congregation of Our Lady of the Retreat in the Cenacle. We turned it into a playpen and recording studio where we were going to work on the album that would be called Draw the Line.

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

At the Cenacle there was the big open room that had been the chapel; only now it had all the pews taken out. There was still the stained-glass windows and the high ceiling, and because of the natural echo, we set up my drums right on the altar. Steven was on the second floor. Brad was in the living room. Joe was in a huge walk-in fireplace. Jack Douglas, the producer, set up his controls in another room with video monitors so he could see us, only we couldn’t see him. Trouble was, by that time the band was falling apart at the seams. The only thing connecting us was the headphones, and that’s the way everything sounded when we played it back. We had really made it now, but we had no idea how to handle that success. It had been such a long fight, and in our mirror we had won, but now what? We’d rented out this fancy place, but we didn’t have a plan. We also didn’t have enough new material, so we wound up doing covers of “All Your Love” and “Milk Cow Blues.” Basically, we spent six months and half a million dollars to make a record that everybody was going to hate.

We had been on the road for two years, and we had all gone insane. Joe showed up in a Porsche and carrying a Tommy gun. He and Steven had always been into guns and knives in a way that was probably a little too intense. At the Cenacle we even had a firing range in the basement and Steven and Joe would blast shit down there for hours.

Given how out of control everyone was, there was a lot of down time. I would wash all the cars just to keep busy, or we’d have water balloon fights. When we got bored, Tom and Brad and I would race up and down the Merritt Parkway in our Ferraris. Then we would come back and decide that driving 130 in traffic wasn’t enough of a release to deal with our frustrations, so we took my cymbals out and shot at them with shotguns. Meanwhile, Joe was firing pistols in the attic and drinking White Russians for breakfast.

One time Steven and I were up all night on coke and Tuenols. About 10 a.m. he decided he wanted some outdoor target practice. We went down the hill to the other end of the property, and Steven lay down on his chest in a sniper position with the .22. I started setting up beer cans as targets, but I was so wasted I never noticed that I was setting them up so that we were firing toward the house. After I was done, I stood back and said, “Let ’er rip.” Steven was aiming…and aiming, but he was taking so long I began to wonder what was going on. “So shoot already!” I said. Then I walked a little closer. That’s when I heard the snoring. He’d fallen asleep lying on the ground with the rifle in his hands.

Jack was like the den mother for our little troop of bad boys. I’d come downstairs in the morning, and he would say, “We changed the figure for this song. We want you to do it this way. Go in the room and learn it. You have two hours.” Then he’d hand me a two-gram vial of coke. “Here’s your medicine.” So I’d go off to the room with just me, my drums, and the stay-awake.

Brad and Tom and I were drilling to stay tight, but Steven and Joe wouldn’t even show till midnight. Joe, when he did show, was usually too fucked up to play. Jack would chew him out, so then Joe would go back to his room and disappear for days. He didn’t even play on all the songs we recorded. He just didn’t care anymore, and neither did Steven. We were pissing away everything we had worked for all those years, and yet everybody was yukking it up like we were nine years old at a summe

r camp that would never end.

We had these caterer chicks cooking for us who had worked with the Grateful Dead. For dessert one night they made us brownies and milk, and after they put dinner away, they put this little treat on the big long table that was between the chapel where my drums were and the main living room. The hallway with the big long table connected to the room where Jack was set up with his recording equipment. It was a schlep, so every time I walked back and forth between the chapel and Jack’s location, it was very easy to just pick up one of those little brownies and chuck it down. So every time I walked back and forth, that’s what I would do. And we must have done six or seven takes, and after each take I’d walk back to the control room to listen, and I’d grab a brownie on the way. Then I’d walk back to my drums to do the next take, and I’d grab a brownie on the way back. Around the sixth or seventh take I looked up at the monitor and said, “Jack, I don’t feel so good. I feel kind of strange.”

I couldn’t hear what Jack was saying back to me because of all the background noise, which was the rest of the band cackling their asses off. Then it occurred to me, why is everybody in the playback room, and I’m the only one sitting out here ready to play? Fact was, Jack had filed away the take he needed hours ago. He had just been replaying the same thing over and over, getting me to play to it again and again, so he could get me to go back and forth eating those fuckin’ brownies on my way to the studio. They were laced with so much pot. This must have been what Tiger, my Great Dane, felt like the day he got on top of the fridge and ate a whole pan of hash brownies. He was just about comatose. We had to carry him outside to pee.

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

The last day at the Cenacle, we tried to film a commercial. They were trying to shoot a scene of Joe riding his motorcycle up a ramp into a trailer, but he was so fucked up, we had to shove some coke up his nose so he could stand. He drove the bike up the ramp and right off into the bushes. The video was never used.

That last day had been a long one under the lights, and that last evening we drank a lot of Jack Daniels. I was really anxious to get home, however, and I was looking forward to the ride in my Ferrari. There was no way I was going to stay over till morning. Brad offered me some stay-awake, but I turned it down because I didn’t like to do that stuff while I was driving.

Around eleven o’clock I started heading north, and in front of me was about 150 miles of freeway. I cruised up through Connecticut, crossed into Massachusetts, and then with just about forty miles left to go, I hit the 3000 mile mark on my Ferrari. This meant that it was officially broken in and I could now open it up. This was at two o’clock in the morning on the Massachusetts Turnpike somewhere near Framingham, with nobody around. All the lanes were clear, so this was definitely the time to see what this car would do. So I eased it up to about 130…135…then…and the rush I felt—like flying—was definitely part of what you pay for. It was especially sweet at that time of the morning, being all alone, but I told myself, Okay, don’t push your luck. So I eased over into the right lane, and I was just kind of cruising along; I came up behind a truck that was going a lot slower than I was, which is just about when I noticed that I was once again not feeling too great. All of a sudden I felt really, really tired.

Smashed and crushed metal woke me up. I’d rammed into the back of this guy. The Ferrari was so low to the ground that I actually slid under the truck, which crushed the windshield. Fortunately, the impact lunged me forward into the steering wheel just enough to get my attention. Still, it was all I could do to steer off to the side of the road. I slid into the guardrail, and when I stopped, the impact banged my head against what was left of the glass up front.

I just sat there for a second and caught my breath. There was blood all over the place. Thick, dark blood was oozing all over the silk baseball jacket I had just brought back from Japan. It was all over my pants—all over the car.

I was still sort of stunned, so I sat there for another minute. Then a state trooper came along and asked me if I was okay. He got me to get out of the car and stand up. I turned off the lights, and then I stood there for a second looking at the Ferrari, holding my hand up to my head. Which was when I realized that, wow, I couldn’t see out of my left eye. I thought I’d gone blind in that eye, which totally freaked me out. I was half muttering, standing there at 4 a.m. fumbling through my wallet, pulling out nine registrations for nine different cars, and the trooper thought I was out of my mind. Then I realized how much blood there was, as well as all the glass stuck into my forehead. And when I felt all the blood, I realized that was what was keeping me from seeing. But then the loss of blood started making me woozy, and I thought I was going to check out. I managed to lock up the car, and then the trooper took me to the hospital in his cruiser, bleeding all over the seat.

At the emergency room in Framingham they spent a lot of time picking glass out of my forehead, then sewing it up. They told me the cut was bad enough to sever a main artery. About an hour later, Tom came cruising down the highway in his Ferrari and saw mine smashed into the guardrail. He told me afterward that he really didn’t even want to call the police because from the look of it, he thought I was dead. But he did call, and they told him what had happened and where I was, so it was Tom who came over to the hospital, picked me up, and took me back to his house where I spent the night.

Photographic Insert

Joey in the saddle—Bronx, NY, 1953

The Kramer kids, 1960, Yonkers, NY

Rik Tinory Studio, Cohasset, MA, 1975

Three generations of Kramer—Marshfield, MA on Pudding Hill Lane

Having fun

Photo session at Zildjian

Spacemen

Nothing like playing live

Obligatory publicity photo session

Me and Steven at the Wailing Wall

On the set of the Rugrats

Schwing!

Joey and Keith Garde

Tom and I graced by the presence of Jimmy Page

Book promotion on the Leno show

Cemetery, Japan, 2002

The Kramer kids today

The creamsicle drums, Honkin’ on Bobo tour

We had to cancel some gigs because of this damage I’d done to myself. But to get the story straight, our managers, Steve Leber and David Krebs, wanted to talk to the doctor who was taking care of me. So they came up to Boston. My father insisted on being there too.

The four of us—me, Krebs, Leber, and my father—went to the doctor’s office, and my father sat to my left, Steve Leber sat to my right, and David Krebs sat to Leber’s right. It was a little strange for me that my father wanted to be there, but I was pretty fucked up from the accident so, as unusual as his offer of support may have seemed, I appreciated it. The doctor started in explaining all about heart rate and blood pressure and how, if I played gigs and my heart rate went up, it was going to blow out the artery above my eye, where the stitches were, and that I would bleed, and that it would just keep opening up, which could be seriously dangerous.

Steve Leber looked at the doctor and said, “Isn’t there some kind of IV or something you could hook him up to on stage so he can play?”

I thought my father was going to leap over me and try to choke the bastard. I pushed my dad back into his chair and told him to calm down. It meant a lot to me that my father was sticking up for me, but I remember having this strange, mixed reaction. While it felt good to get his support, I saw in my dad’s demonstration of anger at my manager a glaring reminder that for so much of my life, this same guy, acting that same way, was what I needed to be protected from.

I replaced the smashed-up red Ferrari with a silver one. Somebody told me later that Clint Eastwood bought the wrecked car and had it refurbished. I wasn’t into reclamation projects. At least not yet. Instead, I just kept snorting the lines, and everything kept going downhill.

Draw the Line was still not finished when we left the Cenacle, but we went ahead and toured that summer anyway�

��the Aerosmith Express Tour—doing God-awful shows. Rumors went around that we were breaking up, and by all rights we should have quit, because we had totally lost it musically.

This was when the press started calling Joe and Steven “the toxic twins.” Steven would do something to piss off Joe who would play too loud and ignore his backing vocals just to piss off Steven. When we went to Europe, they started fighting on stage, even down to Steven’s pulling Joe’s amp cord out of the socket for playing too loud. In Belgium it was like World War I with the fans up to their knees in mud, surrounded by barbed wire. The caterers had tied a goat to a table and you had to milk it yourself to get cream for your coffee, so the crew shit on the desk in the promoter’s trailer.

We were in Munich when Elvis died. At the Lorelei Festival, Steven passed out on stage after three songs, and near Frankfurt he started spitting up blood. The Scandinavian part of our tour was canceled, and we still hadn’t finished Draw the Line. I wanted nothing but to go home. This would be our last show outside North America for ten years.

Still, it could have been worse. Zunk Buker was a childhood friend of Joe’s, and his dad, Harold, was in charge of our air travel. The managers sent him down to Dallas to check out a low-budget Conair plane that had come on sale. He looked it over and said no way—he would not fly in it and would not allow us to. Three months later, the plane crashed in Mississippi with Lynyrd Skynyrd on board, killing half of them. There were so many different ways we could have, should have, died.

Hit Hard

Hit Hard