- Home

- Joey Kramer

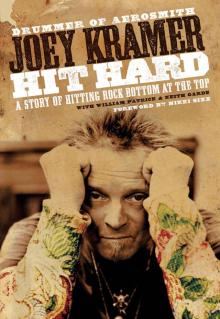

Hit Hard Page 10

Hit Hard Read online

Page 10

In the summer of 1974 we did the Schaefer Music Festival in Central Park. The crowd wanted more Rory Gallagher, the blues guitar hero, and everybody started booing and throwing bottles. Somebody threw a beer bottle up onto the stage, and it landed right on my drums. It cut my arms just as I was about to do the barehanded part for “Train Kept A Rollin’.” I spoke into the mike on my drums and said, “This is for the asshole who just hit me with the broken glass.” And then I played my heart out. The crowd loved it.

More and more, blood and broken glass seemed to be the kind of excitement the fans were looking for. One of the new bands on the scene was KISS, with the makeup and the costumes and the fire swallowing. When Aerosmith and KISS played together, our roadies and their roadies wound up pulling knives on each other.

In September 1974 we were back in Boston to do sold-out shows at the Orpheum. J. Geils, who had produced a top-ten album in ’73, was already sailing into the doldrums, which left us free to take over New England. By the winter our crowds were much bigger, with a lot more excitement. We played Boston College Fieldhouse and caused a bona fide riot.

When it was time for us to record our third album, Jack Douglas put us to work out in Framingham, at Andy Pratt’s studio. Joe came in one day with this great guitar hook. We played with it for a while, and Steven and I worked out a drum part. I was just playing the beat, really. The foot pattern on the bass drum went right along with the guitar lick, and up on top it was just twos and fours, with eighth notes on the high hat, and twos and fours on the snare drum. This was the same sort of beat we had used for “Lord of the Thighs” off the second record.

None of us was thinking that this was anything special. At the end of the day, we had ourselves a nice little number, and we called it quits. We went out to get something to eat, and then we went to the movies. We saw Young Frankenstein—there’s the part where Igor, the hunchback, does the old Groucho Marx gag: he tells the visitors to the castle to “walk this way,” and they follow him with the same limp and lurch that he has. “Walk This Way” became the title of the song we’d been working on. A few days later, Steven had finished the lyrics, and we knew we had something. The song now had an identity, and he was using that same rapid-fire singing style he had used on “Sweet Emotion”—very rhythmical—which makes a lot of sense when you remember that Steven was a drummer. Steven and Joe both base a lot of what they do on percussion, and the fact is that all music is actually just drum rudiments applied to other instruments.

Steven and I worked together on a lot of the rhythmic stuff, and a good idea is a good idea—it doesn’t matter where it comes from. I worked hard and was very disciplined. I wrote out my own arrangements for how every symbol crash was supposed to be orchestrated.

“Walk This Way” appeared on Toys in the Attic, and that album was huge for us. We toured all through 1975, only now, more often than not, we were headlining. As the headline act, you get to have things the way you want them—the lights, the stage setup. But, of course, having too much of what you want can turn you into a crazy person. One day a check came in the mail for $275,000. I went out and bought a red Corvette, which cost just over $8,000—I remember the price of the car because I recall paying for it with eighty $100 bills.

Thanks to Frank, we were blessed with financial obligations that we had to buy our way out of, so we had a lot of Frank’s “friends” still hanging around us waiting to collect. But the mobsters brought along a whole new group of dealers with them, so we didn’t really mind.

With more money in the pipeline, Aerosmith became the single biggest market for drugs in New England.

In 1975 we released a reedited version of “Dream On.” It made the Billboard Top 10. Then we released “Walk This Way” as a single, and it reached number 10. What none of us realized, though, was that we had just reached our early peak. We had two rapid-fire top ten singles, but we wouldn’t be having any more for another ten years. Having hit that peak meant that we were already on our way down. Meanwhile, Frank was dying of cancer, and he sold his remaining share in our management to Krebs and Leber.

By now we had picked up an audience of teenage boys in blue jeans, what we called our “blue army.” The only problem playing to this demographic was all the crap they threw onto the stage, including cherry bombs and M-80s. We took over a warehouse just west of Boston, in back of Moe Black’s Hardware Store in Waltham. It had a stage to rehearse, and it became our place to hang out, sort of a boys club with room inside to park my Corvette. Like most guys who get a lot of fame and a lot of money before they know what to do with it, we carried on pretty much like the thirteen-year-old boys who came to see us.

For five years my biggest concern was, where’s the blow? My entire routine consisted of being on the road and getting high, and I was having the time of my life. I had no sense of our larger career trajectory.

As a drummer, I felt I had proven myself. I had become comfortable holding up my corner, keeping us moving with the rhythm, and I accepted not being in the center of the spotlight. But the guys started bugging me that I should do a drum solo. Raymond, who was still doing marketing for us at the time, started working with me. He laid it out this way: “You have to do a solo the same as if you were writing a song. It’s got to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. And it’s got to make sense. And just when you got them, you don’t keep playing—you stop. You leave them begging for more.” So I put together all my best licks and shaped it the way he suggested.

At the Pontiac Silverdome, in Michigan, it all came together for me when we headlined at our first stadium show, and I did my first solo in front of eighty thousand people. No drug has a rush like that. When the audience responded to me, I could feel the joy in every cell in my body. So being me, I got hooked on that high, and I did a solo every night for the next eighteen years, until drum solos became kind of passé.

Overall, though, my job never involves being the center of attention. Up on stage, we’re five guys each doing his part. Steven’s job—and it ain’t an easy one—is to be the electric focal point every second, exploding with energy. The guy busts his ass like a professional athlete, running from here to there, jumping off of things for hours every night. Joe’s got his assignment as well. He’s got to be a kickass musician, but there’s also a lot of theater, being the sex symbol and playing off Steven on stage and all that.

For the rest of us, we hold it together and keep it running. We’re the linemen, not the quarterback calling the shots, or the wide receivers dancing in the end zone. When Steven and Joe do their “sit down” at the other end of the runway, a hundred feet away from me, I’m doing my job keeping a steady beat and just playing the way I play.

Years ago I had a psychic do my chart, and when she came to see the band, the way that she described it was that we were like a traffic jam and I was a filling station. Everybody is driving around and around, and every once in a while they will come over, fill up, and take off again. I like that role, being almost like the mother hen, so to speak, or, maybe better to think of myself as the mothership.

Even though my real home was on the road, I still needed a place to hang my hat in Boston, so I kept an apartment at 21 James Street, near Coolidge Corner. My landlord was Mr. Chin, who used to come by every month and bang on the door. “Joe Kramah! You pay rent today?!” This was a huge first-floor space with stained-glass windows and high ceilings and enough mahogany for about a dozen cabin cruisers. It was so big that, part of the time I was living there, Raymond and his wife, Susan, lived with me. My girlfriend Cindy Oster, the Playboy bunny, was there, too, and there were a lot of parties with so much constant drug intake that we were really living right on the edge every day. I remember, we had a dentist friend who used to let us use coke in his chair. One day he came to my apartment, and it was all I could do to drag myself to the door. I had been taking Quaaludes and God knows what else, and I could barely move. He saw that I was all but down for the count, so he stuffed some coke up my nose t

o keep me from going comatose. If he hadn’t shown up…hard to say what would have happened. All I know is that it’s a fucking miracle that none of the five of us are dead.

Once while I was on tour, a friend of mine named Scott Sobel was doing some work on the place, and Cindy was there sort of supervising and painting some of the walls. Cindy was epileptic and had to take medication to control it. She and Scott were, of course, also consuming quite a bit of blow, and Cindy had forgotten to take her pills. Scott described to me how he heard this crash, ran into the next room, and there was gorgeous Cindy, lying on the floor frothing at the mouth, her eyes rolled back in her head. Scott immediately called 911, but then when the medics and the cops arrived, he remembered the huge pile of blow sitting on the coffee table, lines all laid out. So he left Cindy shaking on the floor and the cops banging on the door while he ran around the apartment and hid all the coke.

By the midseventies, the drugs, which had started out as a way to cut loose after a lot of hard work, had taken over. Back then, my idea of a Friday night was to hook up with somebody along with an ounce of cocaine, and a nice big quart bottle of Stoli that I kept in the freezer. We would sit, and we would snort, and we would drink, and then we would snort some more. Friday night would turn into Saturday morning, and Saturday morning would turn into Saturday afternoon, and we would still be drinking and snorting—another shot, another line. Saturday afternoon turned into Saturday night, and Saturday night turned into Sunday morning, and before I knew it, three days of my life had gone by. I was sitting in the same fucking spot on Monday morning as I was on Friday night.

Pontiac Silverdome

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

My wake-up call with drugs—at least in terms of the music—came when we played Boston College in 1984. For the three or four nights prior to that, I had been swallowing Tuenols and putting cocaine up my nose and not sleeping at all. By the time I got out to BC, I was fucking blotto. My drum tech, Nils, had to help me take my street clothes off, put my stage clothes on me, tape my hands, prop me up behind my drums, and wrap my fingers around the sticks. “Joey, this is all I can do,” he told me. “The rest is up to you.”

Drums and drugs really don’t mix—the timing, the physicality—so I didn’t play well that night, and my partners weren’t very happy about it. I took heed of that experience, though, and I never again took drugs directly before a performance. On the other hand, I was always able to make up for lost time afterward. As soon as the last note was hit, I would be off stage and catching up to wherever I might have been if I had been snorting like a maniac all along.

After a while it should have been clear that the drugs had become obsessive, addictive, and destructive. But when you’re doing drugs, nothing is clear—that’s the whole point. Looking back now, I realize that even just thinking about doing lines had become an obsession. I enjoyed simply the thought of drugs, relishing the anticipation, then feeling the actual sensations. There was pleasure in all of it, from the first moment the coke burned into my sinuses, as the chemicals slammed into my brain cells, and until I was racing along all grandiose and invincible. I loved the way it made me feel holier-than-thou and how I could sit and talk with anyone about anything as if I really knew it all. And then there was the sort of connection whenever I found somebody else who liked coke as much as I did. Trouble was, while there was pleasure, there was no real joy in it. After a while, drugging became as empty and gross as stuffing my face with cheeseburgers and greasy french fries, eating out of gluttony instead of hunger for nourishment. Eventually feelings of waste, excess, and anxiety crowded out all the feelings of pleasure, but by this time, I had no choice. I was no longer doing the drugs for a good time—I was doing them because I had to. And then the drugs started pulling the band apart.

Krebs and Leber managed a lot of bands, including the New York Dolls, and the Dolls were becoming more and more a part of our scene. Their whole act meant nothing to me, because I was into being a musician and being serious about playing my instrument, and for these guys rock ’n’ roll was all just a freak show. But suddenly we had David Johannsen, their front man—later known as Buster Poindexter—hanging around. Then Steven took up with Johannsen’s girlfriend, Cyrinda, and then Steven and Cyrinda started doing dope with Joe and his girlfriend Elyssa. They were shooting up in New York, and I was putting coke up my nose and booze down my throat in a different space and time, and that separation started to matter. Then Steven started getting weird because Joe was always with Elyssa—a relationship that is a whole bizarre story by itself. So my little surrogate family, this band of brothers that I deluded myself into believing we were, that I thought I had, was really starting to slip away from me.

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

DRUG ADDICTS DABBLING IN MUSIC

5

For a couple of years I had been kind of out of touch with my actual family, but now for the first time I could put my hands on some serious money, so for Father’s Day I went down to see them in Eastchester. I brought along a new car for my father, a brand new Cadillac Seville. I handed him the keys and said, “Happy Father’s Day.”

He said, “How much money do you have?”

I said, “Fifteen thousand.”

“How much did this car cost?”

“Fifteen thousand.”

“So how can you go and spend all your money on a car?”

This wasn’t like, “Ah, you shouldn’t have,” with a hug and a smile. This really was, “You’re a stupid bastard for wasting your money.” All I could see in his reaction was that he and my mother had such a fixed sense of the way things should be that they couldn’t see anything else in this gesture—least of all me. Then I watched as he got in the car and went off to show all his friends.

Obviously, his calling me a stupid bastard was not exactly the reaction I’d been hoping for. Still, one thing my father had any respect for was the dollar, so at least maybe I had registered something with him.

Looking back from my perspective now, it’s pretty obvious that what I was up to was, “Dad, I’m a success. Dad, I have money. Look at what I can do—what I am doing for you.” It was the classic pattern of trying to please the abuser. His reaction was a total letdown, but I handled it the same way I handled everything at the time—I just put my head down and stuffed the emotion. Whenever a feeling reached the surface, I made sure I numbed it out with drugs and alcohol. But now that I had some cash, it became very comfortable to also numb it out with stuff.

I bought a Mercedes so big that it would always get stuck in the driveway of Joe’s place in Newton. The next time I came down to Eastchester to visit my parents, my mother wouldn’t let me park it in her driveway. Being Jewish, my mother couldn’t understand how I could possibly even think of buying a German-made car. Especially a Mercedes Benz. After all, it was the Benz family that made the ovens the Nazis used to murder millions of Jewish men, women, and children.

In 1976 Rocks shipped platinum, meaning one million copies, and we were floating along in the luxury bubble with the women, the jets, and the blow. We hardly blinked when one of our dealers in New York was killed. No big deal. The downside of the drug life had no hold on us. We were invincible. Which meant that we really didn’t notice as everything became more of a blur and the faces all around me starting to look melted like those drawings in an R. Crumb comic book.

Arena rock was all about putting on a spectacle, but with us the over-the-top show on stage wasn’t just the lights and ramps and fireworks. There was Jack Daniels and rum on the drum riser and coke lines on the amps, and God help a roadie who brushed it off or put his flashlight there. Joe and Steven would snort lines between songs—during songs. The rum was 150 proof, and Steven would pass it out to the kids in the front row who’d drink it until they puked. We had girls climbing all over us, but, truth is, a lot of the time we were too focused on the drugs to really care.

On the Fourth of July we could not get a permit for Foxboro because our last tw

o Boston gigs had nearly caused riots, so we missed that opportunity but were earning our reputation as the “bad boys of Boston.” On July 10 we were supposed to play Comiskey Park in Chicago before 65,000 fans when the place caught on fire. Jeff Beck was onstage, and we were waiting in the wings; and our manager freaked out because he wanted us to get started performing so we would be sure to get paid. Problem was that the whole place was on fire, which made it a little difficult to actually play. All the news reports commented on how calm the audience was. Fact is, they were too stoned to react.

About this time Rolling Stone was talking to us about a cover, but then they only wanted Steven, which led to a big fight. The agreement we all had was for Steven to avoid photographers, so they couldn’t get a solo picture of him. But Annie Leibovitz showed up at his room at the Beverly Hills Hotel at six in the morning, banged on the door, barged in, and snapped a picture of him lying in bed. The image that appeared on the newsstands made him look like he’d just (barely) come back from the dead.

When we played the Cow Palace in San Francisco, I wanted to get the crowd all hyped up, so I started throwing sticks out to the audience during my solo. It worked—they went crazy. We played the Kingdome in Seattle before 110,000 kids, but to us the whole show sounded like a remote hookup. The venue was simply too big. Regardless, we were playing some of the largest venues in the world; we had come a long way from the Savage Beast in Vermont.

The only way I can keep the years straight is by remembering which car I was driving at the time, and 1976 was the year that Tom and Brad and I all bought Ferraris. Mine was a black 308 GTB. Even after I placed the order, it still took almost twelve months for it to arrive. I think I paid $29,000 for it, which was serious money at the time.

Hit Hard

Hit Hard