- Home

- Joey Kramer

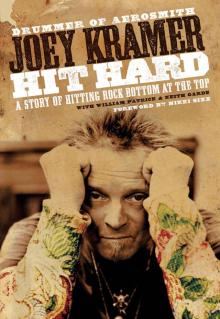

Hit Hard Page 14

Hit Hard Read online

Page 14

To give him his due, it was Tim who laid down the law. A legendary booking agent named Johnny Podell told him, “Look, you gotta clean these guys up.” So Tim came to us and said, “Listen, I can help you guys get back to where you were, but its not gonna happen if you’re still doing drugs.” The way we saw it then, Steven and Joe were the most extreme, so they had to get clean first. Easier said than done. Joe would go into rehab to dry out, then hit the first liquor store the minute he got out of the tank. Eventually Tim started getting Joe hypnotized to see if that would help. Steven was already a rehab frequent flyer. He had gone away to Hazelden, but Krebs had met him with a limo at the airport and had him smoking a joint on the way home. Steven stayed clean about two seconds. But then his heroin connection got murdered down in the Village, in New York City, and something seemed to register. After Steven himself got mugged, he seemed to have more motivation to clean up his act. But this was not before he wound up hospitalized at McLeans, the highly respected psychiatric hospital just outside Boston. Tim found a doctor to put Steven on methadone, then instituted random drug tests. Steven cheated by storing week-old urine in condoms strapped to his leg.

This reformer streak in Tim was a little suspect at the time, because when we first got together, he was somebody I liked to get high with. But it was a blessing he had enough of his rational brain left that he could see what needed to be done and had the balls and conviction to do it. In 1984 he “encouraged” me to move back to Boston by loaning me $28,000 as a down payment for a house. This was where I moved with April and our two little kids—Pudding Hill Lane in Marshfield, on the south shore.

With Brad and Joe back, we had a huge New Year’s Eve celebration at the Orpheum Theatre in Boston. A new light was starting to shine on Aerosmith. We were different, because we had crashed and burned, but now we were coming back. This was the original band from fifteen years earlier, and at first it was mostly we who realized the power of that and the value of what we had. After a while, I think the rest of the world caught on too. One of the critical changes was that Joe realized he was what he was within the context of the band, so there was a little less ego or frustration and maybe more of a commitment. But even with all that renewed energy, coming back was a long hard climb, just like the first time we’d made the trip.

We struggled for another year and a half, and then some rap group we’d never heard of asked Joe and Steven to be part of a video. They were Run-DMC; we didn’t even know who they were, so we felt no big urgency to do this. We sure as hell had no idea how monumental this video and working with Run-DMC was going to be. Although we didn’t know who they were, we figured out how far down we dropped, since these kids had been sampling the riffs from “Walk This Way” for years, and they thought that the name of the band that had done the original song was Toys in the Attic .

The way Joey sees it

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

On March 9, 1986, Joe and Steven taped this session with them. The play on MTV literally put us on the radar screen of this whole new MTV generation and energized our career like a spike full of adrenalin straight in the heart. Joe and Steven were the only Aerosmith band members on the screen; there was a local New York band called Smashed Gladys backing them up—not Brad and Tom and me, but we had bigger things to worry about.

Unfortunately, not even getting a miracle second chance, like Run-DMC recording “Walk This Way” was going to solve our problems. The first road block to solving our problems was drugs—simple as that. Tom, Brad, and I were still using, but that November Brad joined AA. Steven and Joe were still drinking and doping. Our summer tour that year was so bad that Tim called it off.

It’s a big deal to call off an entire tour simply because you’re too fucked up to play, so Tim was determined more than ever to get us clean and sober, and he started learning more about Alcoholics Anonymous. Johnny Podell also introduced him to a therapist named Dr. Lou Cox, who directed the process of our formal intervention on Steven. This was huge. Steven was outraged for being singled out. “Why me?” He pushed back. “You’re all as fucked up as I am.” The irony is that the rest of us were fucked up too. But I’m relatively sure Tim believed that if Steven didn’t get clean, it wouldn’t have really mattered much what the rest of us did. Despite Steven’s resistance, in the summer of 1986, he went away to the Caron Foundation in Wernersville, Pennsylvania, a clinic called Chit Chat Farms, and he got clean. Then Joe went to Bournewood Hospital in Brookline, and finally the idea of sobriety “took.”

Tom and I had always kept the appearance of it more “under control”—at least we looked that way compared to the “toxic twins”—so we managed to kind of roll along for a while longer. Fortunately most of my drinking and drugging was on the road, so my little boy, Jesse, didn’t see much of that. Asia did, and I regret it. But even where Jesse was concerned, I just wish I could have been more present, more “there” all the time but especially in those once-in-a-lifetime moments like when he took his first steps. Not just there, as in not on the road, but “there” in the sense of having my heart connected to my family, of having my head screwed on straight, of having my own shit sufficiently under control that I could be the grown-up, there to focus on him and let him be the child. Still, Jesse was a great kid, even with a fucked-up dad for the first five or six years of his life.

I never, ever sat him down for instruction, but at about age four he picked up the drum sticks and has never put them down. Jesse learned by osmosis. He sat behind me in the basement and watched. When he first started playing, his legs were too short to reach the ground from the stool, so he’d lean up against it, sort of half standing, so he could push the pedals. Like me, his ears are his eyes and his eyes are his ears. He can look and listen and noodle around until he’s got every last detail down pat. When he was around six, I bought him his first set.

In December 1986 I came home one night, and our lovely little house on Pudding Hill Lane was on fire. I had to stand there and watch all our clothes and everything else we owned, right down to the gold records, go up in smoke. The band had just begun work on Permanent Vacation, which would turn out to be our comeback album, but now—personally—I was faced with another mountain to climb. The fire had nothing to do with drugs—the inspectors said it was caused by old wiring. But if anything should have been like a sign or a symbol that I needed a big change and a new start, this should have been it. Instead, even that first night after the fire, when April and I moved into a hotel, we did what we figured every couple does after watching their house burn to the ground—we snorted a shitload of coke.

We got Asia back in school, and then it took me maybe a week or ten days to deal with renting a house for us to move into, salvaging what we could from the fire, renting furniture, and putting that whole picture together. It was like so much in my life—I just put my head down and did whatever I thought needed to be done, but I never really reacted to it emotionally. I never processed it. The fire was just one more big set of feelings that I hid from with blow and Stoli.

We were on even more of a tight budget after that. But we took all the money we got from the insurance company for the house itself and for all these other losses and put it back into building a new place on the same footing as the old one. So we wound up with a decent house, but we still had lots more rebuilding to do in terms of furniture and clothes and our lives.

In January 1987 the band started working in our new rehearsal hall in Somerville, the one with what we called “the wall of shame,” decorated with bras and panties that had been thrown onstage. By the spring, John Kalodner had Steven up at Little Mountain Studios in Vancouver, Canada, doing preproduction. John and I didn’t get along so well at the beginning, but after a while he became a really good friend of mine. John always had very special ears. And, truth be told, he was the principal architect of Aerosmith’s resurgence. He brought in Bruce Fairbairn, who was Jon Bon Jovi’s producer and much more disciplined than Jack. Bruce really kicked us up into a

higher orbit in terms of our sound. Kalodner also brought in Desmond Child as a song doctor to help Steven and Joe on the creative side. Desmond had a real commercial sensibility, and we needed material that we knew was going to yield hit singles for those three-minutes of airplay on radio and MTV. This was a new way of doing an album for us. It was not just thrashing through to the deadline. Instead, it was thinking it through clearly, planning, and executing. There aren’t too many second chances in the music business, and we did not want to blow it.

I remember Steven coming back from the first sessions in Vancouver for the new album. They’d focused on recording the trumpet and sax, and Steven really loved that soul sound, and he knew I did too. So he brought the tracks over for me to listen to, only this time he was sober and I was high. I remember his looking at me and stating the obvious: “Buddy, you need help.”

Tom was still smoking a lot of weed, and I was still into cocaine and vodka, but by this time we were the last two holdouts. Everyone else had gotten into the program. As bass and drums, Tom and I always did the basic tracks first, then they built up the rest on top of that. On the playback I was really psyched, because this was the first record where my drums really got captured well. I was in love with Bruce Fairbairn because he made the drums really big and really present in the mix. The drums were right out front, and I was in heaven.

By starting first, Tom and I also finished first, and we had a tradition of wrapping it up and then saying, “We’re fucking done! Let’s go party!” Only this time, with everybody else already sober, we had to sneak around to do our celebrating.

Not long after that, I was down in Eastchester visiting my folks. It was clear by this time that my dad had Parkinson’s, and each time I saw him, it had gotten a little worse, which was really depressing. I had a lot to say to him, a lot to work out, but I didn’t even know where to begin. Or, at least, if I knew, I didn’t have the capacity to do anything about it, because I was still hiding out in my addiction.

Down in Eastchester, April and I did some heavy drugging over at Richard Guberti’s house, then went back to my parents’ place to spend the night. April went upstairs to go to bed, and I went downstairs with a gram of coke in my pocket. Of course, down in the basement, there was also a liquor cabinet well stocked with vodka, so I was down there all night long.

At ten o’clock the next morning, May 20, April came down and looked at me, and I remember the pity in her eyes. This time it was me who stated the obvious. I looked up at her with bloodshot eyes and said, “April, you gotta help me. Please. I really need some help.”

Courtesy of Gene Kirkland

ONE DISEASE, TWO DISEASE, THREE DISEASE MORE

7

On July 3, 1987, Tim called to say there was going to be a band meeting at his house in Brookline at eleven o’clock. When I showed up, Steven, Brad, and Joe were sitting around the living room with Lou Cox, the therapist who had facilitated the intervention with Steven. We all started shooting the shit, and then the discussion got around to drugs and alcohol, with Lou doing most of the talking. After a while, I could feel the hairs on the back of my neck start to bristle, because the talk was becoming less and less general, and more and more focused—on me.

Okay, I thought. I can see what’s coming.

“You need to enter rehab,” Lou said.

“Like immediately,” Tim said.

I looked at my partners, and they were all sitting there with arms crossed, nodding and looking grim. “That’s the deal,” they seemed to be saying.

I said, “Look, guys…I’ve been clean and sober for three months already.” Since that morning in Eastchester when April found me in my parents’ basement, I’d been going to AA meetings at Green Harbor down in Marshfield. Through the Pembroke Hospital I’d even found a shrink, and I’d been seeing him every week.

“Great,” Lou said. “The fact that you’ve already taken the first steps toward sobriety makes this the perfect time to go away for treatment. You won’t have to go through detox. You’ll be ready to participate from day one.”

I could see there was no point resisting the whole group. But still, there were practical problems. I’d been living in a rental since our place burned down, and we were scheduled to move into our new place literally the next day.

“I can’t go right now,” I said. “I gotta move my family tomorrow. I’ve got to get everything sorted out. I’ll go day after tomorrow. I promise.”

Brad and Joe rolled their eyes. (“I’ll sober up first thing tomorrow” is like the number one classic dodge of the addict.)

“Well, I don’t know if I want to be in a band with you then,” Joe said.

But Steven was different. He heard me out, and I could see that he believed me. He said, “I trust you, man. I know you’ll go.”

And that was it.

The next day came—the Fourth of July—and it was cardboard boxes, moving trucks, pallets, and dollies from dawn till dusk.

We did what we could to settle in, had some dinner and put the kids to bed. April’s brother dropped by, and I went upstairs and started unpacking what I needed from the boxes into a suitcase.

An hour or so later, I came downstairs, and April and her brother were snorting lines off the coffee table. I went back upstairs, thinking, I’m not the only one around here who needs some help.

The next morning I went away to the same place in Wernersville, Pennsylvania, that Steven had gone to, Chit Chat Farms. I was at Chit Chat for a month, and one of my main influences there, and the guy to whom I owe a huge debt for my sobriety, was a Catholic priest named Bill Hultberg—only I had no idea he was a priest when I first started working with him. He was just one of the staffers, and he was a very smart, very insightful man.

Father Bill had worked with Steven the summer before. Bill always used to say to me, “You want the same thing that Steven’s got. But you have to get it yourself.”

He’d say it as a kind of teaser, but he would never explain exactly what he meant. In that respect he was sort of like a Zen master, and I was like the “grasshopper” kid in those Kung Fu shows who needs to figure out the riddle.

Father Bill used to come up to me first thing in the morning and say, “Well, good morning, Steve…ah, Joey!” He would always make this mistake of starting to call me Steven. A couple of weeks into my stay, he did that “Steve…ah, Joey” thing, and I said, “Will you please stop calling me Steven! Don’t do that! That really annoys me!”

This big smile came across his face—he knew that I had finally caught on. It was then that he kind of took me under his wing.

When Father Bill first started asking me, “What does Steven have that you want?” I thought he was talking about the fact that Steven was always center stage, that he was the one who could always say “fuck you” to everyone else and still get his way.

After a point, I realized that all that ego stuff had nothing to do with where Father Bill was trying to point me. What Steven had that I wanted was sobriety. He had been at Chit Chat a year ahead of me, and now I wanted to get clean too. The difference was that, where drugs and booze were concerned, I was so sick and tired of being sick and tired that I only wanted to go through this rehab once. Steven and Joe had gone to maybe five or six different rehabs. But I was so motivated at this point to stop feeling the way I felt and to stop living my life the way I was living it that I went after sobriety the same way as I had always gone after the drugs and the alcohol—like a man on a mission.

I came after Father Bill, asking him, “Why?” I wanted him to explain to me why I got high the way I did. What was the reason?

He told me that knowing why is nothing but the booby prize. You don’t need to know why—all you need to do is work on your issues and stay sober. If you stay sober and work on your issues, then everything else will come to you.

“Angel” video, 1987

Courtesy of Gene Kirkland

That answer didn’t satisfy me, and the question kept gnawing at me,

but after a while I figured it out. Father Bill’s point was that we all like to think we’re so smart that if we can just get to the big answer intellectually, then we can get rid of the problem. He told me that, at least at first, my attempting to “know” all about the source of my problem was just another dodge. He said that if I thought I knew all the reasons why, then maybe I’d think I could get ahead of the game and not have to go through the pain of feeling all the feelings I was going to have to feel. Which is the part of getting sober that takes guts, and patience, and scares the shit out of everybody. But facing all my shit was the only way I could get past it. The road is through, not around. And that’s where having a really good therapist would make all the difference, somebody to guide me a bit and make me feel safe enough to get down to what’s real, to face down the demons and know that I’m going to be okay once I get to the other side.

Father Bill and I talked a lot about authority figures, about boundaries, about love and abuse, and about demons bearing gifts. He starting giving me a new vocabulary, and one of the key words he underlined and kept coming back to was codependency. That was my deeper addiction—the dependence on other people to feel good about myself. He also began talking to me about post-traumatic stress disorder.

Hit Hard

Hit Hard