- Home

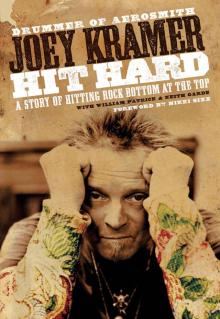

- Joey Kramer

Hit Hard Page 15

Hit Hard Read online

Page 15

According to Father Bill, you don’t have to be a wounded soldier, like my father, or a rape victim to have PTSD; you just have to experience really powerful stuff that you don’t acknowledge and that you don’t deal with at the time. We talked about the way I was treated as a kid, of course, and my anger and my denial about the anger—that I couldn’t accept it and couldn’t acknowledge that these past experiences were affecting me. My reaction to abuse in my childhood was to just bury the emotions and keep on putting one foot in front of the other. I reacted the same way when my house burned down—just get the job done and don’t really react. I’d been doing the same thing for the past twenty years in putting up with the relentless criticism I got from Steven.

Near the end of my stay, Steven and his wife, Teresa, came to visit me, which was really great of them, especially since Steven had been at the same place as a patient not that long before. Permanent Vacation was just about to come out, and he brought me the album cover. April came down to Wernersville with them, and we ducked out to my room for about five minutes—after three weeks of celibacy, it didn’t take long to get to the point of this conjugal visit. The four of us then strolled around the grounds and had lunch, and it was pretty relaxed. Steven and I were psyched, talking about how great Aerosmith was going to be now that we were all clean and sober.

Later, April came back for the Family Program, which has the intended purpose of helping the patient. But while she was there, she realized that she was just as much an addict as I was. A couple of weeks later, she was back for her own twenty-eight-day recovery program.

Being a member of Aerosmith had always meant being on call 24/7. So when I checked out of Chit Chat, I flew directly from Pennsylvania to California to start working on our first real video, which we were doing to promote “Dude Looks Like a Lady.” I really didn’t give it much thought at the time, but here again I was going to simply leap right back into the middle of everything, on a soundstage at A&M, after I’d just spent twenty-eight days in rehab. I had no time to ease back into normal life. Most significantly, I had no time to really feel all the emotions involved in going through this huge change in my life. I had just gone through emotional surgery. Jumping right back into work left me no room and no time to heal.

When I’d first gone to AA back in Marshfield, I did the usual thing—claiming I was there just to check things out for “a friend” who had a problem. But by the time I got to L.A., that was behind me. I found a meeting at a place that was mostly musicians, producers, A&R guys—entertainment industry folks showing up every day at seven o’clock to stay with the program.

At one of these meetings an older lady got up and said, “I’m grateful for my pain.” I was a little confused at first, but after a while I figured out what she meant. What she was describing was what I was beginning to experience, which is that when you’re sober, you can begin to actually feel your feelings again—the bad as well as the good. Even if what I’m feeling is pain, at least that means I’m feeling, that I’m living my life instead of numbing out to most of it. What she was saying, really, was that she was grateful that she had the willingness to feel.

Toward the end of that summer, in August 1987, Permanent Vacation hit the stores. We had our work cut out for us. We had pissed off just about everybody in the record business. We were good at not showing up for scheduled and heavily promoted radio interviews, which made the radio station program directors pissed at the record-label reps for not delivering us and, not to mention, pissed at us. In one fell swoop we would alienate a radio network and the national label reps. Everything is connected in this industry, so the radio stations would get pissed at the label and then refuse to play any records (not just Aerosmith records) from our label as punishment for the fact that we, an artist on their label, fucked the radio station. Then the label would get ripshit at us because we caused this whole thing to happen.

And we didn’t just alienate radio and record people—everyone around us got caught up in our insanity. I remember this one time we had a big band meeting with our lawyers and accountants—kind of a once-a-year review of everything. It was an important meeting with people who were looking out for our best interests. I had been on a binge for the last four days, so I was completely fucked up and out of it when I got there. About ten minutes in I fell asleep. Then I felt our business manager give me a little shove, which woke me up. I was like “what the fuck, man?” Like he should be apologizing for my falling asleep in his meeting. Then he said, “Joey, I think you should go find the bathroom—now.” It took me a minute or two to realize that after I had fallen asleep, I shit in my pants and didn’t even know it. Not a real high point for me, and this is just one example.

We had a lot to make up for. So we put on a full-court press, sending out personal notes and personalized videos to disk jockeys and other movers and shakers and tastemakers in the industry.

The album went on to sell five million copies—definitely a comeback. The “Dude” video—with our bearded A&R man, John Kalodner, in a wedding dress—got big play on MTV, and both “Dude” and “Rag Doll” made the top twenty. We went on tour and did 160 shows. We pulled 65,000 fans into Giants Stadium, then did three sold-out performances at Great Woods amphitheater outside Boston. Our wives printed up T-shirts that had the names of our rehabs printed on them instead of the tour dates. Guns N’ Roses was opening for us. But what was even a bigger change was that now there was this optimism thing going around, and it wasn’t just that we were back on the upswing in the music business. We all felt good physically. We were actually exercising and getting rest instead of staying up all night doping our brains out. There were some strict rules put in place initially, created to provide a protective environment. Crew were not allowed to drink in front of us, and now we had security—our tour manager, a former Arizona state trooper named Bob Dowd—to keep the dealers away. He’d go into our hotel rooms and empty the minibars before we arrived.

I’d been doing drum solos at most every performance since 1976, but now there was a special kind of joy to it. For maybe fifteen minutes the other guys would just clear the stage and leave it to me. There’s usually a ramp up on the back of the stage, and they could hide underneath it and chill, and I could glance down at them through a grill.

For every tour I’d do something different, and this time out I put together this electronic package that could sample drum sounds just through the motion of the sticks—no need for them to actually connect with the drums. This setup included a neoprene belt with transformers, and my tech would put that on me while I was still playing. The sticks each had a vein routed out down the length and a pick-up wire running through it and up my sleeve and down into the belt pack that I wore around my waist in the back. I would get up from the drum riser and start banging the sticks on my body. Then I would walk around the stage where there were kick drums set up at various stations, and eventually I would work my way down to the edge of the stage. I’d start shouting out to everybody, dividing the audience into right side versus left side to see who could make the most noise. Then I’d play with the crowd a little more, standing over the security guy who’d always be there to keep people from jumping up onto the stage. I’d sort of pantomime out, “You want me to drum on his head?” And everybody would scream and holler “YESS!!” And then they’d go crazy with my tapping lightly on his cap but putting off this huge sound. I’d play on his head for a while, then work my way back around to my drum riser. I’d get rid of the belt thing, then go back to playing on my regular drum set, only with just my hands. I’d start working out on the skins like they were bongos, going faster and faster and faster until it was as fast as I could go, and then I would stop cold—and the crowd would go nuts. Then I would do one more thing, going back and forth between the cymbals with sticks, and I would bring it up again as fast as I could possibly go, and the crowd would be yelling with me, and then I’d stop cold again and throw my drum sticks out into the audience, and that was it.

> On stage, March 1988

Courtesy of Gene Kirkland

Me and Joe, 1988

Courtesy of Gene Kirkland

We had an applause meter to measure crowd reaction to this or that, and the drum solo was always the thing that got people fired up the most.

I was feeling good on this tour, but I also knew that you don’t just do twenty-eight days in rehab and leave it at that, good to go, no more problems. The transition from being an active addict to not being an addict is a big deal, and it took me awhile to even discover all the things that were going to be different. And there were other aspects of life that were new as well: I was still getting used to being out of the hole financially, to having a new house, to having a new point of view. For the first time I didn’t have to deal with sneaking around and lying and scheming—all the bullshit that went along with being a drug-addicted alcoholic who was as sick as his secrets.

I’d been “Joey Kramer, the drummer” since seventh grade, and that’s who I was. Even in my own mind I was the drummer from Aerosmith, and pretty much that was that. I guess I saw myself as being a decent person. But my whole adult life had been so wrapped up in the band and drugs and constant excess that I’d excluded and neglected other dimensions. Coming into sobriety and starting to see a shrink regularly was all a pretty big transition, so I was a little overwhelmed, and I think it made me kind of withdrawn. In a way, I was like one of those coma patients who wakes up after twenty years and has to get reacquainted with life. For the first time, I had some inkling of what it meant to be fully conscious, and being conscious included reflecting back on my life and seeing things with increasing clarity—all the passion and all the pain. In my case, I found myself working through some doubts as to whether or not I had made the right moves, the right choices, or gone in the right directions.

A lot of marriages break up within a year after people get clean because, for the first time, they start looking clearly at their lives and their relationships without the distortions from all the chemicals. I’ve seen people who’ve been together for twenty years, and then all of a sudden they get sober and look at each other and say, “Wow, what the fuck am I doing with you?”

For the first eight years that April and I had been together, we had been actively using, so those years really didn’t count much as an indication of how we would be together on our own—meaning without the drugs. I was using when we met, I was using when we fell in love, I was using when we got married, and I was using when our son was born.

It’s also said that when you start using drugs, you stop maturing emotionally, so according to that calculation, I was emotionally about fifteen when the calendar said I was thirty-seven. On top of that, I made my living in a rock ’n’ roll band, which meant I was a complete fucking emotional retard. It’s simply next to impossible to be balanced and normal when your job is playing music in front of 60,000 people at a time.

With the fog beginning to clear, I kept thinking about that Billy Joel song “Honesty,” which was the song that April and I had danced to at our wedding. One day she looked at me and asked if I still loved her, and I said I didn’t know. That was a very honest answer, even though it was definitely not the answer she was looking for. I didn’t know about loving April because I didn’t even know me.

Of course, April was just getting sober as well, and her self-esteem wasn’t that great, so she made an assumption—that my uncertainty had something to do with her, that maybe I thought there was something “wrong” with her. One of the things we’d just begun to learn was that if we were going to be in a healthy relationship, we really had to detach somewhat from the other person’s opinion of ourself. I was learning to recognize that the minute I assumed something about what someone else was thinking or feeling about me and I got into defending against that assumption, not only was I giving life to a committee of enemies in my head, but I was the “chairman” of that committee. Maybe most important, I began to hear the concept that we are not what other people feel about us or think about us. It started to make sense to me that other people see me not the way I am but the way they are and vice versa. This was an extremely difficult concept for me to integrate into my life day to day because up until that point my whole life had been based on pleasing other people and conforming to their expectations and needs. I gave the people around me the power to define who I was—for me—whether they wanted that power or not. And when they did want that power, I was in even bigger trouble.

“I can’t hear you!” drum solo, 1984

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

At that time, April and I committed to working on our relationship, but the first question we faced was, is this thing worth the work? We decided that it was, and we started trying to relearn how to communicate with each other about how we felt, which was not easy for either of us. Neither of us had experienced that kind of open and honest communication in our families growing up. It was a welcome way of doing things, but just being welcome didn’t make it easy.

“Janie’s Got a Gun” video, 1991

Courtesy of Gene Kirkland

We just kept doing it, though, and inch by inch we moved it along. It’s like when you’re trying to lose weight, and instead of looking in the mirror every day, you learn to look at yourself only once a week or once a month. You see the progress more easily that way. The more we worked at it, the easier it became, and the better our relationship became.

But April wasn’t the only person I had to relearn how to be with. After Chit Chat, Lou Cox became my therapist, and I worked with him sometimes alone, sometimes with the whole band, and sometimes with him and just two of the band members, one on one.

As an individual, I had to get clean and sober in order to start addressing underlying issues that, for me, led to depression. For the band, getting clean and sober meant that we could start addressing the underlying issues that had plagued our band family for so many years.

My first one-on-one sessions were with Steven and me. Lou mentioned to both of us that he was very impressed with not only our commitment to working to make things better but also with our seeming to care about each other.

Lou asked me, “How do you feel when Steven comes into the room? How do you feel when you’re relating on a level when it’s really purposeful and productive?”

I told him that Steven was such a creative spark for me that it was exciting just to know that we were going to get together. Steven told him the same thing. So I really believed there was this love and respect we had for each other. But there was also the criticism, which felt abusive. And there was so much more of that than the creative excitement and respect I felt from Steven.

The fireworks could start out simply, with Steven reacting to something I’d played. “Are you kidding with that?” he’d say. He’d give me a look, and I’d say, “Why don’t you just sing and let me play the drums,” and after that all bets were off. With that little prompt, Steven could start roaming back and forth across our whole relationship, and then my upbringing, my sexual history or whatever, piling on everything he knew about me as evidence for whatever claim he was making about what was wrong with me and why I simply couldn’t face up to it. The other guys would stand there, holding their guitars, getting bored, and then one by one they’d simply peel off and leave the room.

One year clean and sober

Courtesy of Modern Drummer.

The trouble was that I gave Steven all that power. I believe he was genuinely frustrated that I wasn’t doing or getting what it was he wanted me to, but at the same time I think he had an idea that I would find what he said and the way he said it hurtful and demeaning, and I don’t think he knew how to stop himself. Looking back, I think he felt shitty about treating me that way and ashamed of his abusive behavior. I didn’t know it then, but I have come to learn that that was the kind of behavior therapists call an expression of self-loathing. It’s about the person delivering the message—Steven—and not about the recipient—me—but I sw

allowed it hook, line, and sinker. I made it about me, and I resented Steven, and I couldn’t process any of it. So I stuffed it all down inside. Sure, I could see that Steven wanted to make things as good as they could be, but I felt so twisted that I could only tell him to go fuck himself, or I’d just shut down—which is what I mostly did.

That said, although it was a little scary, I was happy to work on our personal relationship as just that—a personal relationship—but I also thought we might find a way to improve our collaboration musically. We needed to find a way to get beyond the pathology of his always yelling at me, “Play it this way,” or, “Play it that way,” and my either yelling back at him because his “suggestions” always sounded like put-downs—or my shutting down.

We were all very good at gravitating back toward the original positions we held in the families we grew up in. That was home base, and we were always heading for home. In my case, Steven’s being a mentor to me—sort of like a father figure—got twisted into my giving over my power to him and letting him beat me with it. It was the same old confusion of love and abuse I’d had with my dad. For Steven, I think I was like the younger brother he’d always beat up on, so much so that he didn’t even realize he was doing it.

Steven was an inventively bright, extremely creative, hyperactive kid with an extra added rebellious streak that propelled him to be the superstar he is today. As a kid, his curiosity and passion about whatever was important to him was met with ridicule and punishment by a world that didn’t understand him and confused his intensity with his being a bad kid—a world that would try to shut him up rather than hear, understand, accept, and appreciate him for what he had to offer. But Steven would do whatever was necessary to make sure HE WOULD BE HEARD. We were a perfect match for each other’s dysfunctional, codependent behavior. Working on our relationship, we were all very vulnerable. I needed all the help I could get.

Hit Hard

Hit Hard