- Home

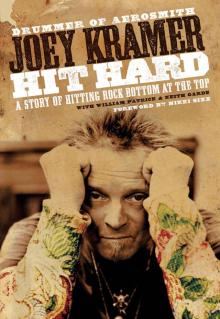

- Joey Kramer

Hit Hard Page 2

Hit Hard Read online

Page 2

New Orleans, 2004

Courtesy of Ross Halfin.

After a few days, Steve Chatoff tracked down April in India, but when she and I talked on the phone we decided—or so it seemed at the time—that she would stay on and continue her trip. She’d waited a long time to see Sai Baba, so when we were on the phone, she told me she knew I was in good hands and questioned what she was going to do back in the States anyway? “Okay,” I mumbled into the receiver. My own wife seemed distant, distracted, and not particularly concerned about me, but this was hardly the first time, so I didn’t think about it much. It would take me another ten years to allow myself to admit that what I really felt was unsupported, unloved, abandoned, and sad, which at the time added far more to the anger I couldn’t recognize and didn’t know how to express.

Of all the people who saw me in this miserable state, the one who reached out to me first was Steven Tyler. Back in Miami, his room at the Marlin was just down the hall from mine, and when I first showed up to attempt to settle in and unpack, his door was open. Even before I went down to the studio, I sort of stumbled over to see him and I told him what was going on with me. I can’t remember what he said, exactly, but it was one of those times when Steven’s compassion and heart of gold really came through. He gave me a hug. This was something I really needed, and at that moment a hug from Steven was more significant than had it come from anyone else.

Steven Tallarico (Tyler); he had been my friend—and truth be told, my hero—since junior high school. Steven was a couple of years older and always cool, the tenth grader with the Beatle boots and the voice that blew people away. The voice—and the attitude—that made him the one guy everybody knew was going to be a rock star even before he started to shave. Steven had music in his bones. He was a drummer before he became a lead singer. As such he became my mentor…a mentor I’d always been a little overeager to please. From the earliest days of Aerosmith, I would play something, hoping to impress Steven. He’d look at me and say, “Are you kidding with that?” I valued his opinion, but it always came as criticism. And coming from Steven, the words sounded like my father whacking me in the back of the head. “Stop sniffling!” my father would say, and then the whack! “This report card is unacceptable,” and then the whack! “Your behavior is hurting your mother.” Whack! Whack!

With Steven it felt like the same thing. He was the dominant force in the band “family” with great expectations for the band that he loved, as well as for everyone in and around it. But Steven could be punishingly critical when those expectations weren’t met—“Joey, this sucks; your ideas suck. It should be like this. Why didn’t you think of that? You suck.” Whack!

Steven Tyler and I had been doing that same love/abuse dance now for a quarter of a century. It flowed right out of the dance between my father and me that contributed to my confusion between love and abuse right from the start. The sense of rejection I felt and had no idea how to “name” or express just collected inside, seeping into every cell in my body. Maybe that’s where some of that spring-loaded stuff came in. All the emotion—anger and humiliation—had been building up, packed in tighter and tighter, pressure building up for years until it had to come gushing out. I’d been stuffing more and more anger, humiliation, sadness, and confusion into the same space for forty years, and now it finally busted loose in the lobby of a Miami hotel.

If April had been there, she’d have been telling me to “talk to Baba.” She’d tried earlier to get me on board with her spiritual quest, but I resisted. Now in this state of mind I’d buy into the tooth fairy if I thought it might make me feel better. At this level of misery I had no more resistance, only helpless resignation. I felt a desperate need for some high-powered help, so sitting in my room, I actually muttered a little prayer to Baba…sort of a “gimme a sign” prayer. Then I went down to the common room just so I wouldn’t be so alone.

For once the place was empty—the TV wasn’t even on—so I sat on the couch, and on the coffee table in front of me was a book—a Dean Koontz thriller. I picked it up for no particular reason and started thumbing through it. A bookmark fell out. I looked down at it. A piece of paper—about three by five inches. Then I picked it up and looked again. It was a photograph of Sai Baba. I gotta admit it kind of freaked me out.

I asked around in the cafeteria and found out whose book it was. I told the kid the story of my praying and then finding the picture, and I asked him if I could keep it. He said sure. Sai Baba was not the higher power I needed, but I wanted to keep the picture more as a matter of “why not” than “why?” I needed to believe in a power greater than myself, and for the moment this one would do.

The routine at Steps was breakfast at seven o’clock followed by classes, exercises, lectures, and group therapy. Every day at nine thirty, eight or ten of us drifted into a classroom-like space and sat in a circle and waited for the therapist to show up, this guy Kevin. Jumpy with anxiety, I would cross my legs one way, then cross them the other way. I would scratch my head, then put my hands through my hair, then cross my legs again and shift in my seat because the demons were eating me alive. But then I would look over and see that the guy next to me was doing the same kind of thing. And so was the girl across the circle from him. So here we were, ten people in a room—all obviously uncomfortable—doing our own versions of a crazed fidget dance.

New Orleans, 2004

Courtesy of Ross Halfin.

I was in my midforties, but most of these other people were somewhere between nineteen and thirty-five. I was the only “inmate” dealing with depression and anxiety as a primary “identifying issue,” as the therapist called it, but regardless, a lot of the people there were looking to me for guidance. Sometimes it felt like they wanted to hear from me even more than from the therapist. I guess in some ways they related to me because I’d been through it. They also knew about the band; our downfall in the early eighties was the ugly stuff of rock ’n’ roll decadence—infamy. Our climb back to rock royalty—unprecedented. And maybe they were just psyched to be in rehab with one of the guys from Aerosmith. At the time, though, I was feeling so low that I clung to any opportunity to feel valuable.

When Kevin would arrive, we got down to business. He would ask a question, and everyone would sink down in their seats unwilling to contribute, but I was motivated to raise my hand. I’d been through these routines before. I think it was less because I believed I could be of service and more because I knew the process, but probably mostly because I wanted to get the process over with.

Kevin would ask for a volunteer to do some “empty chair” work, and I’d be the one to go first. We were instructed to address someone we had big issues with. I went up in front of the group and pretended my father was sitting in the empty chair across from me. And I talked to him, trying to say things I had never been able to say to him in real life. As much as I’d dreaded this experimental exercise and felt like resisting, I started to see a little window of safety and was open to start getting into it.

Nine years earlier, when I was at the Caron Foundation in treatment for drug and alcohol abuse, having finally decided that snorting $5,000 worth of coke every week was a bad idea—more on that later—my mother came to visit during family week, and she opened up a little, telling me things about my childhood; she left me with some images from my earliest days. One story she told stuck with me in such a big way that it lodged in my soul even if I was too young for the actual experience to be etched into my conscious memory. I was two years old, she told me, sitting at my dad’s desk. “Exploring,” is what she called it, only this desk was where my dad sat to do work when he came home. Apparently I wanted to sit at this desk and “do work,” to be just like my dad. I pulled out some drawers, and I messed around some papers. I was having a great time, my mother said. But then my dad came into the room. He started shaking me, screaming at me, hitting me.

“What’re you doing!? Get the hell out of there!”

As the words left my mother�

�s lips, I could see that little kid, shocked and terrified. I wanted to scream. I wanted to save him. I couldn’t say a word, but all of this made such perfect sense to me. Hearing her talk was like watching a photograph come to life in a developing tray, the empty spaces filling in over time. This feeling of being cowed and beaten was something that was reinforced in me all my life. This was my father; he was supposed to be my protector, and here he was raging, beating me. This shit was repeated so often when I was a kid that I developed an autoresponse like one of Pavlov’s dogs. The scientist rings the bell when he sets out the food, and the dogs salivate. After a while, the scientist doesn’t have to show the food anymore—the bell is enough. My dad would yell and then—boom—the fists landed. After a while the pain registered in my body whether he hit me or not. Before long, he didn’t need to hit me. And then, he didn’t even need to yell. His mere presence was enough to feel like danger. People react differently to different stimuli. I internalized the madness. I went numb. I’d just keep my head down to try to avoid the pain, and when the pain came, I’d find a way to hide to make it go away.

As a little kid, I’d hide in the crawl space in the attic next to my room and play with my cars. As a teenager, I found my drums to hide behind. As an adult, I added drugs and alcohol for refuge, and I could afford a lot of it. After a while, the job of numbing was complete: by numbing myself to the painful emotions, I had become pretty much numb to every emotion. What had happened to me was that I had to hide to experience pleasure, and after a while I became hidden even from myself. But now the feelings that had been stuffed down inside of me were exploding. The pressure in the cooker was rattling its lid and it was going to keep my guts twisted in knots until it was reckoned with one way or another.

My life had become a series of emotional contradictions. I’d played my drums in front of eighty thousand screaming fans, and passed out in my own puke. I’d toured in private jets, rode in limos, and had just about any girl, at any time, for anything. I had also lived in rat-infested, shithole apartments, got caught in a burning car where I got third-degree burns all over my body, racked up hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt, and watched my father die a slow, agonizing death. But I had never felt anything like this depression that brought me to Steps. All my life, whatever problems or challenges I had to face, there always seemed to be some way out. I could withdraw, hide, or deny, and problems would seem to go away, or someone else would figure out a solution for me so I didn’t have to deal. This time there was only me and my personal pain, and I didn’t see any way out.

In a real way, Aerosmith had also become an addiction. I needed it. It was another place to hide, but like any addiction, instead of providing me with a safe haven, it was beating the shit out of me. Therapists tell recovering addicts that they can’t simply go back to the same crowd they used to get high with—no question, with Aerosmith I had been breaking that rule for decades. The band was my life, but it was also a source of pain, humiliation, and abuse. I started to think that if I really wanted to get serious about healing myself, I might have to kiss Aerosmith good-bye. I needed to see what the rest of life was like, what people call “real life,” without the security blanket of a tour schedule and the drum riser and all the attention. So I decided I was primed and confident and more than ready when we started our group session that day, ready to face my fears and demons and break away from all my abusive addictions. At that moment I began to realize what I would soon discover was a gift—desperation. So I was ready, that is, until Kevin the therapist pinned me to the wall.

Courtesy of Ross Halfin.

“Who are you, Joey Kramer?” “Who are you without Aerosmith?”

I was forty-five years old, and it was time for me to have an answer. This book is about how I came to grips with that question and how I managed to change the way I saw myself in the world. Through the process of learning and self-discovery, I have managed to transform my relationship with myself and, as a result, transform my closest and most painful relationships—Steven Tyler, my father, April, those people whose judgment I turned into a weapon that I stepped in the way of as if on cue. I no longer have to see myself in that role as victim—a major pattern in my life that I really had to get to the bottom of and take responsibility for.

Obviously, coming from the drummer for one of the biggest rock bands in history, this book, like any good rock ’n’ roll memoir, has stories about how we made it and lost it—life on the road of excess. But this book isn’t just about living the rock-star life—there are plenty of books around that are just about that. The real point of this book is to say that you don’t have to be a rock star to crash and burn. The details of our stories may be different, but as humans, our pain is the same. I've been through the fire and have come out the other side alive. Better than alive. And so, by revealing the details of my story in Hit Hard, I tried to convey a story that—while uniquely mine—is so relatable that it serves to deliver a universal message of hope and the process of healing.

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

TWO IMPOSTERS–LOVE AND ABUSE

1

When I grew up, in the fifties, I lived with my family in the Bronx, and then in Yonkers, New York. It was my mom, my dad, my three little sisters, and little Joey always running around getting into trouble. If that sounds like the setup for a sitcom, there was not much of a laugh track.

My dad, Mickey, was a hustle and bustle businessman, a salesman who started a company called Jumbo Advertising. If you were a contractor and wanted ballpoint pens with your outfit’s name on them, my dad would make them for you. Or the calendars that the insurance agents handed out, or the metal frame that went around the license plate that said the name of the car dealership, Mickey was the man! He worked his ass off all week long but on Saturdays he couldn’t wait to get the hell out of the house to go play tennis. I remember his skinny legs sticking out of those white flannel shorts as he passed through the kitchen in his sneakers and matching gym socks.

My mom, Doris, stayed at home and took care of my sisters—Annabelle, Amy, and Suzie—and me. She even wore dress-up dresses during the day, like Harriet Nelson from Ozzie and Harriet, and she loved music and Broadway musicals. When she was younger she practically lived at Radio City Music Hall. Around the house she was always singing show tunes from The Sound of Music and South Pacific. She could even tap dance. She loved the whole idea of show business, the glamour of the world of entertainment, provided that you didn’t push it past Gene Kelly or Julie Andrews.

My grandparents on both sides were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, so both my parents were first-generation Americans. My mother’s mother was maybe eight when she landed in Pittsburgh, and her father opened a shop repairing watches and guns. My father’s father came over from Poland as a kid and found work as a tailor in New York City. My mother used to tell us stories about how her mother scrubbed floors to get through the Depression but set aside quarters so she, little Doris, could take dancing lessons. And how, “of course,” all her clothes were hand-me-downs.

This whole immigrant experience shaped my parents and how they tried to raise me. They were all about assimilation and material gain—fitting in—and image meant everything to them and was pretty typical for parents in the fifties, which also helps to explain why we had “the sixties.”

My father joined the army during World War II, and the night before he shipped out, he asked my mother for a date. They hit it off, and then my mother joined the army, too, working at an air base in South Carolina. But then my father hit the beaches at Normandy on D-day, and he got shot up all to hell and was hospitalized in England. My mother wrote to him, and my dad wrote back. When he returned to the States, they picked up the romance. After a couple of years they got married, and my dad went into the clothing business which he soon determined was not for him. So he scraped together a little money from friends and, with the help of a GI loan, started Jumbo Advertising. And with another GI loan my parents bought a h

ouse at 115 Whitman Road in Yonkers.

My dad was determined to make something out of nothing, and before long, to add to the pressure, he had a lot of mouths to feed. He also suffered from what today we call PTSD—post-traumatic stress disorder. He’d been badly wounded, and many of his buddies were killed. I think he spent a lot of time agonizing over why them and not me? These were only some of the demons that haunted him. I learned from my mother when I was in treatment the first time that when he was just a little kid, my dad’s own mother told him she wished he had never been born, that she had tried to abort him by jumping off a kitchen chair.

Mickey and me, 1952, Bronx, NY

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

I’m sure knowing that can fuck you up, so maybe all of this shit combined was where some of the rage came from, the rage I first experienced at age two when I pissed him off by messing around at his desk. I never knew where it came from, and he certainly never told me, but I felt my father’s anger just under the surface every day of my life.

Our neighbors, the Suozzis, had five kids, and when I was about kindergarten age, their cat had a litter of kittens. I can remember playing in the backyard and finding an arrow lying on the ground. I picked up the arrow, picked up one of the kittens, and stuck the arrow down the back of the kitten’s neck. I have no idea why I did that. The kitten started howling, and all the Suozzis came running out into the backyard, all freaking out when they saw what I’d done. They screamed at me like I was an axe murderer: “Joey, what’re you doing? My god, you’re killing that poor kitten!”

Was I just angry? Or reacting to how I was feeling at home? Maybe I was just a little kid doing the kind of mindlessly cruel things that little kids sometimes do. I don’t know. But I do know that I had powerful feelings that I couldn’t name, feelings that surely I had no idea how to process.

Hit Hard

Hit Hard