- Home

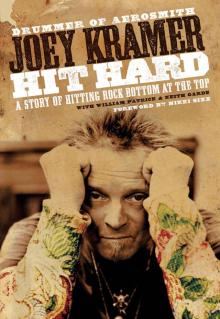

- Joey Kramer

Hit Hard Page 3

Hit Hard Read online

Page 3

Mickey and Doris, young love

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

My dad just seemed pissed off at me all the time, and the next thing I knew, my mother was taking care of my baby sister, and then another baby sister, and then one more.

For whatever reason, I definitely got the feeling that I was not exactly what my parents had hoped for. While I had no conscious understanding of that, all I knew was that it felt bad. I was, however, developing an instinct for making bad feelings go away as quickly as possible.

At home in my bedroom there was a crawl space that I could get to through my closet. The entrance was like the portal to that magic kingdom of Narnia in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, except that the only thing behind the door were my slot cars. Whenever some friends of mine, or their parents, got tired of their Aurora racecar sets, they gave them to me. I wound up with what seemed like miles of track, dozens of cars, and extra controls, so every time I felt bad, I could sneak back into the closet and be all by myself. I sat and played with those cars for hours, hiding out. And I would convince myself that nobody knew I was in there, which made me feel safer still. No one was hitting me or yelling at me. I felt really good, connected and “in the zone.” The only problem was that I had to hide in this space—my space—in order to feel that way.

My dad used to keep a Nestlé Crunch chocolate bar in the refrigerator that was his and his alone, and one night I ate it. He went nuts trying to figure out who took the candy bar. He said that my sisters and I had to stay in and we were going to be punished until somebody confessed. He was pissed. I was freaking out. I headed right up to the crawl space—lots of track, lots of cars. I got lost. My little sister Amy took the blame just to get it over with. She knew she wasn’t going to get hit. Somehow, my dad’s anger didn’t get focused on my sisters the same way it did on me.

When threats were purely physical, like in the neighborhood out in the open, I did a better job of standing up for myself. John Pascucci lived next door, and he was bigger than I was and was always picking on me. One evening in the summertime the Suozzi kids, the Pascucci kids, and the Rosenblatt kids were all out playing in the street, hitting a tennis ball back and forth with rackets, and when it was my turn, John came at me saying, “Give me that racket, you little animal.” He reached out to grab it, and I smashed his hand. He started yelling, “You broke my fingers! You broke my fingers!” I didn’t break his fingers, but I did hurt him badly enough that he never bullied me again. I was sick of being pushed around every day, and even I knew there were fights I could win—and fights I couldn’t.

Mickey “Jumbo Advertising” Kramer

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

Whenever my dad wailed into me, he narrated the experience using all the clichés. “I’m doing this for your own good,” he would say as he hit me. And even when he wasn’t hitting me, he went off at me in such a crazy way that I was sure I was about to die. The tsars back in the old country used to line up troublemakers for fake executions as a way of breaking their spirits. My dad’s rage and his size delivered the same message to every part of me: “I have the power over life and death.” And when I couldn’t keep back the tears, he made it clear—I’d better stop crying, or else.

I had this sniffle—a nervous habit that I still have to this day—and every time I sniffed, my father smacked me on the back of the head. And each time he smacked me, he’d remind me, saying, “Every time you sniff, I’m going to hit you on the back of the head.” Then he’d remind me once more, just in case I could ever forget: “Every time you sniff, I’m going to hit you on the back of the head.”

My dad never asked, “So what’s with the sniffle? What’s going on?” It never seemed to occur to him that my sniffing was a nervous habit and that there might be more to it, that maybe he had something to do with it. He’d just whack me. “Stop sniffling. It drives me crazy. I can’t stand your sniffling.” Sniffle—whack!

My friends knew about my dad, how afraid I was of him, and so they’d fuck with me. Mickey had a special whistle, and when I heard that whistle, it meant I had to come. Sometimes my buddies would get quiet, look at me, and say, “Did you hear a whistle? Joey, I think your dad’s calling you.” I’d go pale, and then they’d laugh their asses off. I’d laugh, too, but, secretly, I would always be listening for that whistle.

Tennis on Saturdays

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

At Jumbo Advertising, Mickey did everything himself—the production, the sales, the bookkeeping—a one-man operation. Sometimes in the summer I went with him to visit clients, and I was always amazed at what a nice, smooth, loveable guy he was with them. He would really charm these people, and they really seemed to like him too. But the Mickey I got was the enforcer: distracted, angry, and generally disappointed and disapproving.

To the extent that our household was pretty miserable for me, school was more of the same: more disappointment, more disapproval, and more physical punishment. Mr. Schwartz, the science teacher, and Mr. Ianocone, the coach, would swat certain kids with these long wooden paddles made from baseball bats split lengthwise, and my ass was always getting blistered. I definitely played the class clown—or the class pain in the ass, depending on how you looked at it. At Walt Whitman Junior High I would screw around in the hall until I was late, and then the teacher would have to send me back to the preceding class to get a late pass. If I could get the pass, I’d come back into the room and make a big production out of it, then sit in the back and start drumming on my desk, certain to be annoying.

For Mr. Hamill’s math class I never had my homework. I was never prepared, and I would always lean back on the rear legs of my chair with my legs hooked underneath the desk. I’d rock back and forth, and every once in a while I’d fall over.

Mr. Hamill would give me a little whack with his ruler now and then to keep me in line. But one day I was doing my usual thing, sitting way in the back, tilting my chair, giving him some lip, but something was different. He didn’t hit me, but he kept warning me, saying “You’d better watch out.” It was weird because warnings never came without rulers before. About three-quarters of the way through the class I happened to glance up and through the glass panels in the wooden doors. Oh shit, I thought. There was my mother looking back at me. She was standing out in the hallway, catching my whole act. So when I got home that day, I caught hell from my father. He may have been the enforcer of the punishment, but my mother was control freak number one. She wanted things her way, and when she didn’t get her way, she talked to my dad. They made quite a team.

The one teacher who sort of “got me” taught ceramics. Mr. Rothenberg must have been six foot six and had a huge hook nose. It seemed like every time I was sent down to the principal’s office, he’d somehow show up to put in a good word for me. He always seemed to know when I was in trouble, and he seemed determined to save me from Mr. Ramano, the assistant principal, who had a major broomstick up his ass and preyed on my fears, fed my doubts, and reinforced my insecurities. Maybe it was that Mr. Rothenberg was a hands-on kind of guy and sensed that I was the same. All I know is that, instead of moving around and taking a different shop class each semester the way you were supposed to, I stayed in ceramics for the whole three years. I must have made more salad bowls and ashtrays than any other kid in the history of Yonkers. Mr. Rothenberg taught me everything he knew about throwing pots and curing them, and would pat me on the back after I created some new design or color. After a while he had me making all the glazes for the whole school system—all by myself. For those three years, he was like a really tall guardian angel. At that time he was the only person who reached out to me, and I felt like I had value and purpose and could make a meaningful contribution. Sometimes I wonder what would have happened had Mr. Rothenberg not been so kind to me and had I not been willing to accept his kindness.

With the exception of Mr. Rothenberg’s class, I didn’t get any (positive) attention, guidance, or support fr

om school authorities—probably because I didn’t fit in there, just like I didn’t fit in at home. The only place where I felt safe and where I completely belonged was with my buddies in the neighborhood. There were six of us—Robbie Kelly, Jack Conroy, Mickey McCullough, Butch Holland, Ricky Zarameda, and me—and we all lived on Whitman Road. We hung out in one another’s houses so much that we knew one another’s moms, and everybody knew everyone else’s brothers and sisters, and everybody’s dog knew everybody else’s dog.

A typical Saturday morning was me getting up and walking down to Jack’s house, which was ten houses down from mine. He was three or four years older than the rest of us. Jack had his license and a ’61 Ford convertible, white with red interior. I’d never knock on the door. I’d just go inside and call to him upstairs, and then he’d come down, and we’d walk back up toward Kelly’s house. After we got Kelly, we’d go across the street and get Butch and then go next-door to get Zarameda, and then we’d all pile into Jack’s car.

I remember this one particular Saturday that was like 100 percent Norman Rockwell. We drove up to the Croton Reservoir, up where the dam is, and we all went skinny-dipping. There was even a tire swing hanging from a tree, and I spent hours swinging out over the water on that thing, letting the momentum take me up to the top of the arc, and then letting go. I’d fly through the air in a forward motion like Superman until I splashed down into the water. Ice-cold!

I didn’t think about getting yelled at, had no worries about taking a beating. I could just be me, flying through the air. Mostly I felt safe, surrounded by this band of brothers. This gang was like my real family, the first environment where I was accepted for who I was. This was a good feeling that didn’t require that I hide, and the “band of brothers” was a concept that stuck with me.

With my parents, being accepted—even being tolerated—meant coloring well within the lines. So I think they were pleased when I approached them about taking accordion lessons. I had a couple of friends who played, and I think the nerdiness of the accordion really appealed to my parents’ sense of respectability. I mean, good luck getting laid with an accordion strapped to your chest. Every Saturday morning my father drove me down to the Joey Alfidi Accordion Studio in Getty Square in Yonkers. I’d go into this little room with a guy, and he would give me a lesson. When I got home, my dad said I had to practice “while the lesson was fresh on my mind.” He’d send me down to the basement, where we had a playroom with a playpen for my baby sister. “Okay, it’s now ten o’clock. For the next hour, you’re not coming out of that room.”

My dad’s intentions were good, and he took the time to drive me back and forth, but there was something about the whole routine that was more like dog training than trying to find out what was inside me and then bringing it out in the best way. As a result, the “forced feeding” method of musical instruction didn’t really take.

Down in the basement we kept a record player and an old upright piano. I had a buddy named Jerry Rosenblatt who had turned me on to the heartthrob singers of the day, guys like Paul Anka and Fabian and Bobby Rydell. I was supposed to be practicing the accordion, but instead I’d put “Lonely Boy” by Paul Anka or “Like a Tiger” by Fabian on the turntable. I’d get up on the piano bench and pretend I had a microphone in my hand, singing, “I’m just a lonely boy, lonely and blue…” I even put a box in front of the bench to make a step so I could make an entrance onto my little stage. For the hour that I was locked in the basement, I was Paul Anka or Bobby Rydell or Fabian or Joey Dee from the Starliters. I was singing my heart out, imagining that I was in a big club and everybody was digging the shit out of me.

Jerry’s brother Allen was trying to make it as a doo-wop singer, and Jerry’s father, Phil, was a heavy jazz cat who taught music in school. There seemed to be something musical in the Rosenblatt gene pool, and what really impressed me was Jerry and his violin. He was totally dedicated to it, and he practiced like a maniac. His father and his brother Allen both played the piano, and they all really seemed to love what they were doing. The discipline of practicing didn’t seem like it was forced on them from outside by somebody else. It came from inside, because something about the music and the way they presented it reflected who they were. In a sense, they were being free to express themselves and disciplined at the same time. Something about that appealed to me, as did the idea that you could be “in the zone” and away from all your troubles, but also creating something.

Jerry was probably the most musical kid in school, but the coolest kid was Frankie Re. He had a waterfall hairdo and was really good looking, and sometimes he wore a sharkskin suit with a black velvet collar. He even had a go-cart with a McCullough engine on it. All the girls liked him, and he got along with all the guys. Frankie had a little combo. He was the drummer, and for Christmas his father bought him his own set of drums. I had to see them, so one day I went over to his house to check it out. I went down into his basement, and there before my eyes was this beautiful set of blue sparkle Slingerlands.

Frankie sat down and rolled out some basic patterns, and then he said, “Try it.” He got up and said, “Go ahead Joey. Try it out.”

This was the first time I’d ever seen a set of drums up close and personal. The blue sparkled, the chrome reflected the light, and there was a little crest on the front of the bass drum with Frankie’s initials: FR.

I sat down and picked up the sticks. Frankie showed me where to place my right hand and where to place my left hand, and then I started to tap around the way Frankie’d been doing. I figured out how to bounce one stick and then the other and to take it from drum to drum. Up to that point I guess I was like any other kid who picks up a set of sticks. You watch somebody play, and it looks like a lot of fun, so you bang around and make some noise.

Then I really whacked it, and it was a rush like nothing I’d ever felt before. Right there in Frankie Rae’s basement I was thinking, This is good. This feels really good.

Frankie took over again, while I sat and watched him play. I watched what he did with his feet, and I dissected it all—took it apart. He let me play again, and I remember it like something out of that movie Billy Elliot. They ask the ballet kid what it feels like to dance, and he says it feels like flying. For me, though, the feeling was more like electricity.

Everything I’d experienced up to that point, all the emotions I couldn’t articulate or even process or understand, I could feel being channeled through those two wooden sticks and onto the heads of those drums. The positive and the negative charges just came together and made a full circuit. Pounding on those drums flipped the switch, and the lights came on.

I had some money from odd jobs, and I talked my parents into letting me rent some equipment—a three-piece set of red sparkle Kent drums. I kept them for about three months, and I began to teach myself how to play. When I could accomplish even the smallest thing, like putting a hand and a foot together, it felt the way I had felt on that rope swing up at Croton when I reached the top of the arc. I was flying, because as I was teaching myself, I was also learning about myself. I was good at this, naturally good, and the more I realized how well I could do it, the more that made me want to be even better. I was a “feel” player right from the start. But when I held the sticks in the traditional grip, the kind that Frankie told me to use, it just didn’t feel natural. In the traditional grip you hold the stick in your left hand almost like a pencil sideways to your body, and you rotate your wrist to make the stick go up and down. But I liked to hold the left stick the same way I did the right, straight ahead as if I’d picked it up to throw it, which is called a matched grip. And this let me hit the drums with both hands really hard, and the inflection of the power got me off. I was nearly thirteen years old, and I was beginning to make the drums sing.

Joey “Davey Crockett” Kramer—fifth birthday party

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

Hormones were kicking in around this time, and the power and the self-discovery of the

drums was really potent stuff for me. But turning thirteen, and especially being Jewish and turning thirteen, presented a few other issues which I had to contend with.

Sittin’ on top of the world, 1951

Courtesy of Doris or Joey Kramer.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays every week, after six or seven hours goofing off in the classrooms over at Walt Whitman in Yonkers, I had to make my way over to the synagogue and spend another couple of hours in Hebrew school, then another hour or so learning to read from the Torah. I was, if anything, probably less inclined to sit still and absorb this kind of education than I was the regular kind. All I wanted to do was be back in the basement, playing my drums.

I met this kid, Sandy Jossen, in Hebrew school—and we became obsessed with minibikes, so much so that I let my drum rental lapse. That one summer we rode those things everywhere, engines screaming, tormenting the neighborhood—or so we hoped. But by the fall I was ready to reconnect with the drums, only this time I wanted to own my own set.

By selling my minibike, which I’d bought largely with my bar mitzvah money, I was able to buy a three-piece Ludwig kit with single heads and a clamp that held the tom-tom onto the bass drum. This was definitely bottom of the line, but I would lie in bed at night, thinking about them and how I was going to work to get the next piece. I’d take on some little job and make a few bucks, and I’d go out and get a high hat, and then another cymbal, and then a stand. Whereas most guys had pictures of movie stars or cars or baseball players on their walls, I had pictures of drums. I had found the thing that brought my life into focus, the thing that motivated me and started to give me a sense of identity.

Meanwhile, the music world was just about to explode. A band from England was creating a bigger buzz than Elvis—Brits who looked like little choirboys in their suits and ties, only they were belting out “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” and “Twist and Shout” rock ’n’ roll. The stuff they were writing was harmonically way beyond what we were used to. They were really a band, too, not just a heartthrob singer and some anonymous backups—the Crickets, the Belmonts, the Jordanaires. The Beatles were the total package, complete musicians as well as singers. They shared the stage, rotated the lead, then shared the limelight offstage.

Hit Hard

Hit Hard