- Home

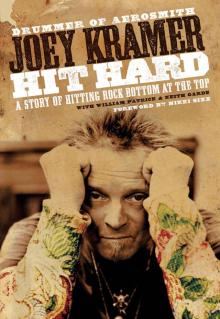

- Joey Kramer

Hit Hard Page 9

Hit Hard Read online

Page 9

The next day John handed us a management contract from Frank Connelly, the Boston impresario who had brought the Beatles to Fenway Park. He had also promoted Chicago’s last tour. It was Frank who had been, at John’s suggestion, sitting out there listening to us. After that, John became our road manager.

Driveway at Cenacle—Draw the Line

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

When Frank talked to us for the first time, he said, “We’re going to win all the marbles.” But for us “all the marbles” just meant being able to make music, to get paid for doing it, and to not have to do anything else. Once we started getting money on a regular basis, the expectations increased, and the reality expanded. Over time we figured out, “Oh, we don’t all have to live in the same apartment.” And then the expectation grew to, “Oh, I guess I can have a car.” And then it reached, “Oh, I guess I can have a nice car.” And then, “I guess I can have more than one car…and maybe they should all be Ferraris.”

Even though money was never the primary motivating factor, it was still a huge thing when Frank started giving us checks. He got bookies and gangsters lined up as investors in the band, and before they all moved down to Providence or into the witness-protection program, they used to come to our shows. One of them ran a ticket agency in Boston, and Frank used to send me down there to pick up packages. Another one of these guys called me once instead of Frank because this package needed to get picked up and Frank had disappeared and this guy didn’t know where he was. When he called me I thought, that’s funny, usually it’s you guys who make people disappear.

Frank had us playing some pretty gamy places, some of which he owned, such as a dive called Scarborough Fair, on Revere Beach, which is to Boston sort of what Coney Island is to New York City. The clientele was mostly bikers, greasers, mobsters, and girls with really big hair. We had a rule that, when you heard gunshots, you didn’t go take a peek out front to see what was going on—you just made a beeline out the back door.

Bob Kelleher, also known as Kelly, was our road manager at the time, and I can’t remember where this was, but I do remember his having to go in after a gig somewhere and collect the money at gunpoint because they refused to pay us.

We did a lot of touring around in New Hampshire in our school bus, playing at venues ranging from Dartmouth College mixers to real bucket-of-blood blues bars. We played a place up there called Savage Beast, where there was a cottage out back for the bands to stay overnight. We nearly rocked that little cottage right off its foundation. It may be true that what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, but what happened in New Hampshire is that most of the guys came back with the crabs. I was still on my best behavior back then because of the hepatitis, but at the Shaboo Inn in Connecticut they had these really cool, colorful light bulbs, and I got busted for stealing some of them. Trust me—that was the least of our sins at the Shaboo Inn.

After the school bus died, Frank rented a car for us, a Delta 88 about the size of a Greyhound bus, in which we barnstormed the Northeast. One day we had some shitty little gig down in New Jersey, and we were barreling down the Jersey Turnpike in this big Buick, and whoever was driving—I can’t remember—was swigging some grape juice out of a bottle, which looked like drinking while driving, so we got stopped by the cops. Next thing we know, we were all being searched and then taken down to the state-trooper barracks and getting booked for possession. Everybody but me. I was the only clean one—again, I was still recuperating—so I was the one who called Frank and got him to bail us out. Even so, the other guys spent several hours chained to some benches while the cops went running out with shotguns to deal with the Camden riots. When we finally got to our gig, there were maybe ten people there. When we got to court, everybody got six months’ probation.

The first big show we did was at what used to be called the New York Academy of Music. We were the opening act for Humble Pie and Edgar Winter. From there we went on to opening for everybody from the Kinks to Three Dog Night to the Mahavishnu Orchestra.

We were grounded in kickass blues and hard rock, but it was getting to be 1972, and glam and glitter were coming on strong. The new acts—David Bowie, T. Rex, the New York Dolls—were big on theater, with lots of spangles and spandex. In music, just like in any other competitive field, you can get blown off the road by changes in taste even before anybody knows who you are. So we kept our eyes on the prize, and we kept refining what we were all about.

Frank was just a local promoter from Boston, but at least after a time he had the foresight and the lack of ego to say, “I’ve brought you along as far as I can. Now you need to go with somebody bigger.” He introduced us to these two big-deal talent management guys from New York, David Krebs and Steven Leber, who had been at the William Morris Agency and had booked the Stones on their 1969 tour. They also controlled the touring company of Jesus Christ Superstar. In other words, they had the money, contacts, and other resources to take us all the way—provided that we delivered the goods.

Frank continued to co-manage us, and one of the first things Krebs and Leber delivered was to get us rehearsal space in the visitors’ locker room at the Boston Garden. Then they got us a gig at Max’s Kansas City, where they arranged for Clive Davis from Columbia Records to come hear us play. Davis offered us a contract, but it was Krebs who signed the agreement, not us. When Columbia paid money, all the money went to Krebs, and then Krebs would distribute it, putting the five of us all the more distanced from the source.

Even so, each of us started pulling down a salary of $125 a week. This was just about the same time that our lease was up at 1325 Commonwealth Avenue. We were about to get the boot, we now had money to live on, and I was ready for a change anyway.

One of the first things I did was to move in with my girlfriend, Nina Lausch. She had her own place a little farther out Commonwealth Avenue, she had a car that she let me borrow, and she had a real job—she was a secretary at an insurance company. This was my first experience of living with a woman, and it was great. I was getting laid all the time, and she had a regular schedule, so when she’d come home, she’d even cook meals for me. I’d had enough of living in one room with Steven. But for Steven, my moving out meant that he was going to have less control over me and this change in how Steven saw the order of things did not help to improve our relationship.

One night at about two in the morning he called me and told me to come pick him up on a street corner somewhere off Huntington Avenue. When I got to the place he said he’d be, he was standing there with a huge string bass, taller than he was. I was driving a little Vega station wagon at the time, and he had already started putting it in the back before I could get out to say “what the fuck?”

“No questions,” he said.

After he loaded up this huge hunk of wood, he got in and we drove off, and right away he started in ragging on me about my girlfriend—the one I had just left in bed in the middle of the night to come pick him up and drive him home. “You gotta concentrate on your work,” he said. “You gotta practice harder. No love involvements.” I looked over at him like, you fucking asshole, are you fucking kidding me? and I told him to shut the fuck up or I was going to put him out on the side of the road. He said, “You wouldn’t do that,” and then he jumped right back in, telling me all the things that were wrong with me. One more time I told him to shut up or I’d throw him out, and one more time he said, “Nah, you wouldn’t do that,” and then he went right back to lecturing me about all my shortcomings. After the third time I told him to shut up, and the third time he blew me off, I pulled over to the side of the road and said, “Get out of the car.” I got out, pulled the bass out of the back and gave it to him. Then I drove off and left him standing there on Route 9 at about three o’clock in the morning, bass fiddle and all. I kind of couldn’t believe I’d done that, and instead of feeling good about standing up for myself, I felt this growing, nagging sense of, “Joey, this isn’t good. You’d better apologize.” The next day, I did.

You might think that it should have been pretty obvious to me that Steven was simply my father all over again, raging at me, berating me, telling me I had shit for brains and constantly ragging on everything that was wrong with me. But at the time, it was not obvious at all. I was so unconscious in those days that I was like some mouse in a lab experiment.

In other ways, Steven could have been channeling my mother. He shared the same element of fakery or creative manipulation that she’d always used in order to take advantage of my emotions. The pathetic thing was—I accepted that too. The mouse wants to get to the cheese, and I wanted to get the love and the acceptance. For the mouse to get the cheese, he may have to go across this metal plate where he gets an electric shock, but if he’s hungry, he’s got to eat, so he just keeps accepting the pain as the price he has to pay. The abuse in so many of my relationships never registered with me because I was so used to it; it was normal for me. Cheese and pain, love and abuse—that’s just the way it’s always been. I didn’t know I had a right to anything better or, really, that anything better between people actually existed. That was a lesson I needed to learn. Even more fundamentally, I needed to learn—and this wouldn’t come for years—that I was the one giving these other people permission to fuck with me, as well as the ability to exercise control.

1978, Meadowlands, ticket sales were falling

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

Fortunately, the young women in my life were very different. They were generous and loving, and I was very lucky. One of the great things about Nina was that she would even take care of my dog, Tiger—a Great Dane—whenever we were on the road.

Like most couples at that age, Nina and I broke up after a while, and when we did, I moved back in with the band. But by that time we had a better apartment in Cleveland Circle, which is in Brookline, farther from the center of town and closer to Boston College.

1977 Ferrari 308GTB—my first Ferrari

Courtesy of Ron Pownall.

I dated a lot of other great women during those years, but I never lived with any of them. There was Jane Cowley, who was a friend of Tom’s wife, Terry. There was Lucille Aletti, and then there was Cindy Oster, a Playboy bunny, who I stole from Brad. There was Margie, and a beautiful girl named Andrea Fox who was a BU student and lived upstairs from Tom and Terry. The sweetest thing is that they all took care of Tiger, sometimes for months at a time.

With Aerosmith, right from the start, it was clear that most of the focus on stage and in interviews was going to be on Steven and Joe. I would not have objected to getting some of that attention, and at first I didn’t fully understand why I didn’t. It took me a long while to understand the reality of the role they played in the lineup and the separate reality of what I contributed.

One day right at the beginning, when we were still rehearsing at the Fenway Theater, our manager, Frank, was talking with Joe and Steven, and Tom and I overheard him telling the front guys that they were the fuckin’ stars of the show, and that Brad, Tom, and I were just lucky to be along for the ride. These comments were like a kick in the gut. I was angry and hurt, and my feelings really never got resolved. No one even apologized or said it wasn’t so. We were the less important three, the “LI 3.” The only way that it got resolved was by my getting to the point of understanding that this is simply the way people are going to look at me as a member of the band, as the drummer. No matter how dedicated you are, or how good you are, and no matter how much your playing contributes to the distinctive experience people associate with a certain band, there’s a difference between being a side man and being the front man. If I wanted to do what I was doing, this was the way it was going to happen, and this was the way it was going to be. I just had to accept it.

Our first album came out with Columbia in 1973. The producer was Adrian Barber, and we recorded it in about three weeks at Inter-media Studios on Newbury Street in Boston.

Except for “Walkin’ the Dog” it was all original songs. Then again, there are only eight songs on the record. It was a good effort, but it was released head-to-head with Springsteen’s first album, also for Columbia. We got absolutely no attention, and it seemed like overnight we started seeing review copies in the used-record bins. We had been allowed onto the bottom rung of the show-biz ladder, but that didn’t mean we couldn’t be flicked off it like a bug. We knew right away that we were going to have to fight to keep going.

At least that first record allowed us to land a tour with Mott the Hoople. At the time, they had a big hit that Bowie had written for them, “All the Young Dudes.” They also had a fan base of teenage boys that we were eager to win over. We were on the road with Mott the Hoople for the better part of two years, which is where we got our first taste of living in hotels, all the while taking lots of drugs and fucking just about every girl that came close. One night, when we were doing some serious drinking with one of the guys from Mott the Hoople in his room at a Holiday Inn, he poured a bottle of booze down the back of the TV. This was our invitation to earn some of our rock ’n’ roll pedigree, and we proceeded to go about throwing most everything in the room out the window, but before anything could go out, it had to go through the TV screen. Stupid, yes, but perhaps less so than if we had trashed one of our own rooms.

The guys from Mott were not that great as musicians, but observing them helped me see what a band could be. I never considered Dale Griffin, their drummer, to be all that talented, but what he did suited their sound and contributed to what they were trying to accomplish.

When we toured with the Mahavishnu Orchestra, which was sophisticated jazz fusion—Miles Davis stuff—once or twice, they actually paid us not to play. Their leader, John McLaughlin, would always ask for a moment of silence before they started in, but after we’d played, nobody could sit still. Their drummer, Billy Cobham, was just fucking amazing. He was the first to use polymetrics, which is to say all the different time signatures at once. We joined the tour in Buffalo, and the first night I walked onto the stage to look around, and sitting on this big Oriental rug was a set of maybe fifteen Fibes drums. They were made out of this Crystalite stuff that you could see right through, and he must have had three or four toms and multiple high hats and a couple of bass drums. I’d never seen anything like it. I thought, So this is like the same instrument that I play? Hmmm. Interesting.

Later on I watched him trade licks with McLaughlin, who was one of the most influential jazz guitarists of the day. They would lock eyes face-to-face and play these abstract, single notes together, going a mile a minute. It was all an improvisation, but it was so tight and so right-on that it sounded as if they’d been rehearsing for years. The rhythms were so complex that I didn’t even understand what they were doing. I’d be standing behind them listening, and I couldn’t even find the “one.”

On the tour, Billy and I compared notes on nitty-gritty shit like how to avoid blisters, but also on techniques for things like doing a simple shuffle. That was something I was really good at and he had a hard time with, so we traded pointers. The tour took a break for about ten days, and when we came back, I’d picked up a set of Fibes just like his, and he’d traded in his Fibes for a set of wooden drums like the ones I’d been using.

We toured next with the Kinks, which bumped our fee from $300 to $1,500 a night, but it’s a funny thing how a band can slide up and down the hierarchy, sort of like when the Beatles opened for Roy Orbison, but then after a few weeks the lineup was reversed, and Orbison was opening for them. Some of the acts we opened for treated us with respect; other times I think they saw us as a threat and tried to keep us under wraps, like the Mahavishnu Orchestra cutting back our time and the Kinks cutting back our space on stage.

Now and then it felt like we were getting somewhere; at other times it wasn’t so clear. And it’s not like you get lifetime security as a rock ’n’ roll band just because you have a record deal. Clive Davis was given the boot shortly after signing us, and word was going around that Columbia was cutting back

, so we had plenty to be nervous about.

Fortunately, we started getting major radio play in Boston, where WBCN would host “battles of the bands.” They set us up against Peter Wolf and J. Geils, the other local band that was big at the time. In May 1973 “Dream On,” a song off our first album, was the number one single in Boston. We were still getting no airplay nationally, so we worked with what we had and made the most of our opportunity to be the local rock ’n’ roll heroes. We did free concerts in the parks all through that summer, drawing maybe two thousand people each time. In August, we opened for Sha Na Na at the Suffolk Downs Racetrack, and thirty-five thousand people showed up. That made the local Columbia Records promo guys take notice, and the label started to kick in on our behalf. Ten months after its release, Aerosmith, our first album, hit the charts at number 166.

After we built up that strong base in and around Boston, we went to the Midwest and started building a base there, too, city by city. They loved us in Detroit, because we had a gritty, blue-collar sound. Jack Douglas, when he came on as our producer, was ready to take that sound and punch it up to a higher level. We would always choke in the studio when the red recording light came on, so he had them put tape over it so we couldn’t see it. Jack wanted Aerosmith harder, louder, more kickass. I already held my sticks backward, hitting hard with the thick end to get more volume. I was hitting so hard that I started using tape and Band-Aids and wearing gloves, but he still wanted more.

In March 1974 we released Get Your Wings, and we knew this was do or die. We also gave the record company a little more option time to continue our contract with no extra payment. We toured all of 1974 and nearly killed ourselves, but the album hit the charts and was on all year. We were like a drugged-out circus act, going from town to town with two tons of gear in a forty-foot tractor-trailer. Except in Boston and Detroit where we headlined, we were still opening for other bands. We toured so much that when I got home, I’d pick up the phone and try to order from room service. But even with all that, Get Your Wings peaked at number 100. Still, that represented half a million copies, which made it a gold record.

Hit Hard

Hit Hard